Working as Intended Legislative Intent, Policing, and Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Frank R. Baumgartner, Marty A. Davidson, II, and Kaneesha R. Johnson

Under advanced contract, University of Chicago Press. (Submitted for peer review, December 2025.)In this book, we make use of a comprehensive database covering every arrest over seven years in a single state, providing a comprehensive look into a state’s criminal legal system from start to finish. How many people are arrested for which types of crimes? Who are those people: rich, poor, young, old, male, female, black, white, Native American, or some other race, residing in urban, rural, small towns, or a big city? What are they charged with? What are the consequences of these interactions with the criminal justice system? Are individuals punished in similar manners for similar crimes? Do the poor and the wealthy come out of the process with similar outcomes? Who gets a lawyer, who defends themselves, and who is assigned legal assistance by the court system? How often do people go to trial before a jury, and how often are they found innocent at trial? Do those who plead guilty before trial come out better than those who maintain their innocence? What punishments are eventually meted out? Are there systematic or idiosyncratic disparities in who receives harsher or more lenient treatment, and who escapes law enforcement altogether, though they may violate a law?

By describing from head to toe the internal workings of the North Carolina criminal legal system, we seek to understand how the state constructs social orderings. Which groups does the legal code target and which ones does it protect? Which behaviors are outlawed, and which crimes have enhanced punishments depending on the characteristics of the victim? Did the state legislature intend for this targeting (and protection) to occur, or do any observed disparities represent an unintended consequence, a simple artifact of differential behavior? That is, we seek to understand whether observed disparities are mere coincidences, or whether they represent the result that the state legislature had in mind when it outlawed this or that behavior.

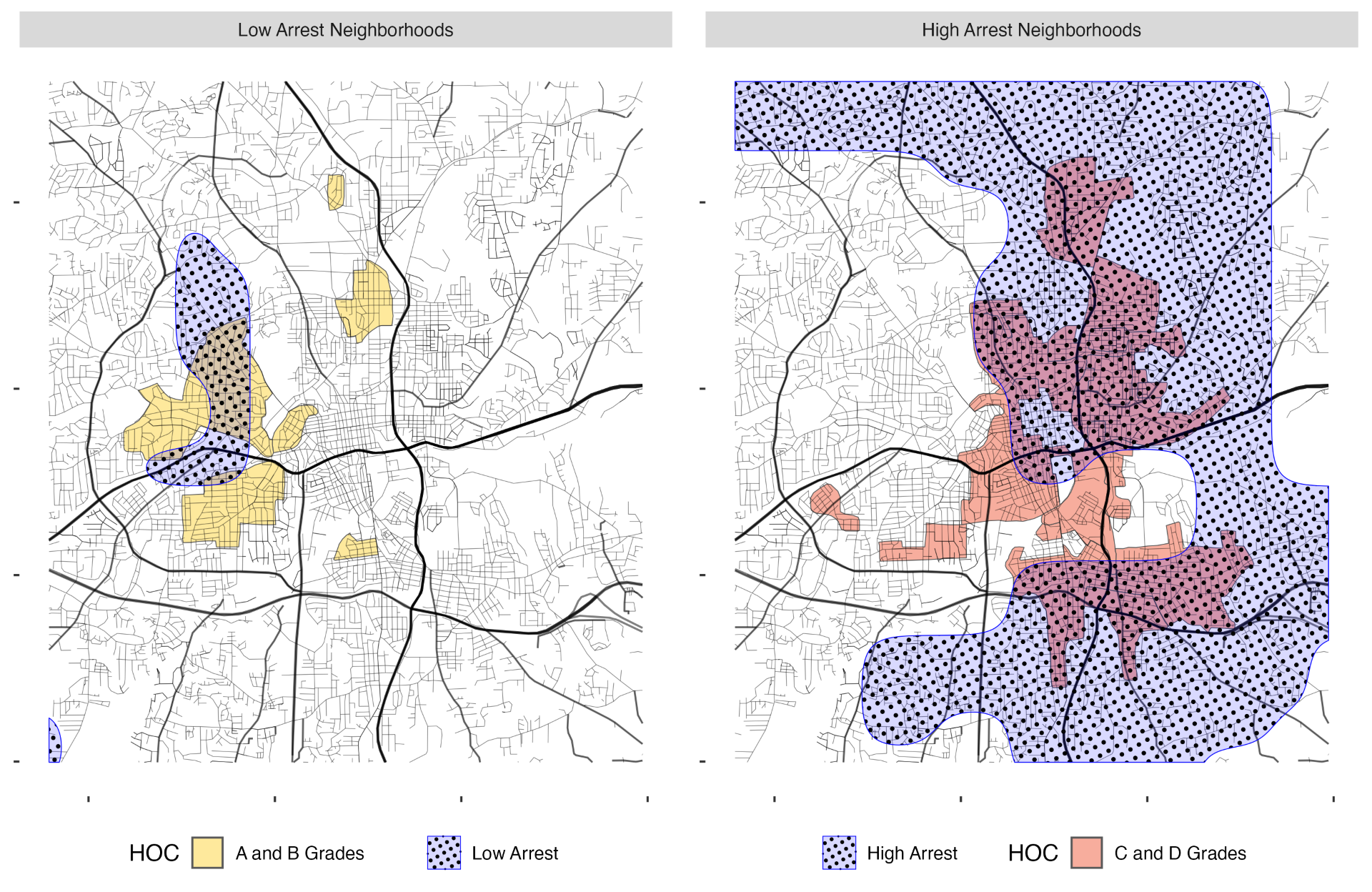

Disparate Impact: In a first section consisting of multiple chapters, we focus on documenting the disparate impacts of various parts of the criminal code. We break down the population into more than 50,000 identity-based groups based on race, age, sex, and geographic place of residence and show vast differences in annual rates of arrest. We show how different groups tend to be arrested for different types of crimes. We show how policing patterns lead to tremendous levels of surveillance in some areas but how the police rarely venture into some other neighborhoods. We document that these patterns are consistent with the historic "redlining" patterns of bank loans in the 1930s: Those areas previously described as "undesirable" developed various levels of under-investment, lack of jobs, and concentrated poverty and marginalization, and these are still visible today in high arrest rates, particularly for those who are marginalized by race. In sum, we document various forms of disparate impact in this set of chapters and review the empirical evidence about the court system and how it works. This section of the book relies on analysis of millions of court records and highly sophisticated geo-spatial and statistical analyses.

Discriminatory Intent: Having documented various specific forms of disparate impact, we move in the next group of chapters to evaluate the intent of the legislature when various laws were enacted. We first explain existing scholarly and judicial definitions of discriminatory intent; demonstration of such intent renders a law unconstitutional. We then expand on these definitions to consider the likelihood that vague or overly broad laws would be expected to be implemented by law enforcement in ways that are detrimental to marginalized individuals, particularly Black people. Finally, we assess the implications of inaction by the legislature when evidence of disparate impact is widely known or presented directly to the legislature. Inaction in such a situation when a feasible revision to the law is possible constitutes a signal that the disparity is welcome, not repugnant, to those who control the legislature. In this section we then review historical and archival records to discuss the origins of the traffic code (1937), laws about protesting (1969), capital punishment (1976, 2009, 2011), gangs (1990s), drugs (1980s, 1990s), structured sentencing with its emphasis on prior points and the creation of a class of "habitual felons" (1994), and other examples. In each case, we show that race was a fundamental part of the conversation during the time when the study commissions were evaluating the problem to be solved, that racial differences that would likely lead to disparate outcomes were known to the legislative drafters at the time of crafting, and / or that legislative drafters were in close contact with law enforcement actors, but not with representatives of the communities most likely to be affected by the laws.

The result of this combination of statistically sophisticated and qualitatively rich analysis is a troubling portrait of a system donig exactly what it was designed to do. We present the racial disparities in the criminal legal system not as a flaw, but as the intent of the system. In the end, we propose reforms that could keep us all safter, provide greater confidence in the justice system, reduce the scope of the law, and promote racial equity. Our assessment of criminal legal system makes clear that that system is embedded in other systems, such as housing segregation, economic and educational disparities, transportation and health-care systems, that all contribute to unequal outcomes. While our focus here is on the criminal legal system, any solution to these issues that would be likely to work should also address the broader structural issues of which the criminal legal system is but one part.

We received an advance contract with the University of Chicago Press for the book based on an initial book proposal submitted in 2022, which is available here.

We submitted the full manuscript to the Press in December, 2025, and we expect to complete the book based on reviewer comments and finalize for publication in 2026.

The figure above shows two maps of Winston-Salem. On the left we overlay a map showing areas of the city with the lowest arrest rates (blue with dots) with the areas of the city identified in the 1937 redlining map as most desirable (A and B grades, shown in yellow). On the right, we show high-arrest areas, with those areas identified in the 1930s as least desirable (e.g., the redlined areas, shown in red). We show similar analyses for each major city in the state in Chapter 6 of the book.

Click on the links below to read various preliminary reports and publications:

Social Identity, Law Enforcement Capacity, and Criminal Justice Contact. Paper presented at the American Political Science Association annual meetings, Los Angeles, August 31 – September 3, 2023. (Marty A. Davidson II, Kaneesha R. Johnson, and Frank R. Baumgartner)

Discriminatory Intent in the Creation of the North Carolina Traffic Code. Paper presented at the Midwest Political Science Association annual meetings, Chicago IL, April 13–16, 2023. (Kaneesha R. Johnson, Frank R. Baumgartner, and Marty A. Davidson II)

Disproportionate Criminal Justice Contact: A System Working as Designed?. Journal of the Center for Policy Analysis and Research 2024: 48-65. (Marty A. Davidson, II, Kaneesha R. Johnson, and Frank R. Baumgartner)

Finding Discriminatory Legislative Intent when Criminal Justice Outcomes Show Racially Disparate Impact. Paper presented at the Midwest Political Science Association annual meetings, Chicago IL, April 7–10, 2022. (Kaneesha R. Johnson, Frank R. Baumgartner, and Marty A. Davidson, II)

Social Identity and Criminal Justice Contact. Paper presented at the Midwest Political Science Association annual meetings, Chicago IL, April 7–10, 2022. (Marty A. Davidson, II, Frank R. Baumgartner, and Kaneesha R. Johnson)

About the authors:

Frank R. Baumgartner is the Richard J. Richardson Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He received his BA, MA, and PhD from the University of Michigan (1980, '83, and '86).

Kaneesha R. Johnson is Assistant Professor of Political Science at UNC-Chapel Hill. She received her PhD in Government from Harvard University in 2023, her LLM from the University of Chicago in 2022, and her BA from UNC-Chapel Hill in 2016.

Marty A. Davidson, II is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He received his PhD in Political Science from the University of Michigan in 2023 and his BA from UNC-Chapel Hill in 2016.

Together with Arvind Krishnamurthy and Colin Wilson, they are also the authors of Deadly Justice: A Statistical Portait of the Death Penalty (Oxford University Press, 2018).

(Last updated, December 12, 2025 )