8 Years and Counting...

What Will Speed Development

of an AIDS Vaccine?By the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, May 1999

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Executive Summary

- Recommendations

- US Government

- Industry

- Not-For-Profit Organizations and COMMUNITY Advocates

Funding Research and Development

Advocating for Research Priorities

Mobilizing the Public

Supporting Ethical and Scientifically Sound Research- For More Information

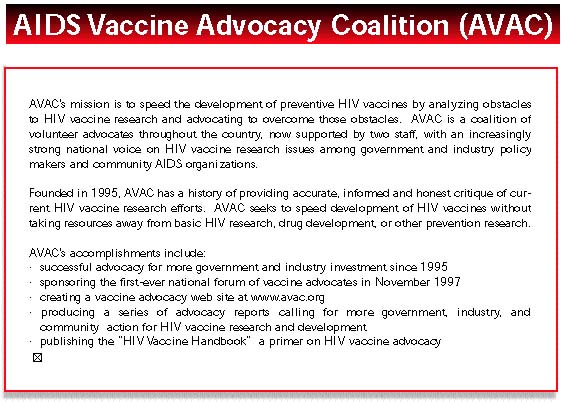

The AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition

AVAC's mission is to speed the development of preventive HIV vaccines by analyzing obstacles to HIV vaccine research and advocating to overcome those obstacles. AVAC is a coalition of volunteer advocates throughout the country, now supported by two staff, with an increasingly strong national voice on HIV vaccine research issues among government and industry policy makers and community AIDS organizations.

Founded in 1995, AVAC has a history of providing accurate, informed and honest critique of current HIV vaccine research efforts. AVAC seeks to speed development of HIV vaccines without taking resources away from basic HIV research, drug development, or other prevention research.

This annual report chronicles events during the past year, with an emphasis on the major obstacles and opportunities in HIV vaccine development. AVAC is a United States advocacy group and this report focuses largely on the efforts of our government and communities. This is not to ignore the fact that the challenge and effort for an HIV vaccine are international in scope, and that advocacy must focus on the global effort. Toward that goal, we hope that this report furthers dialogue and progress in the many organizations whose missions relate to combating the HIV epidemic.

Contributors to this report were:

Sam Avrett - Washington, DC

Dana Cappiello - Woodside, CA

Scott Carroll - Washington, DC

David Gold - New York, NY

Adrian Marinovich - New York, NYLuis G. Santiago - New York, NY

Bill Snow - San Francisco, CA

Jim Thomas - St. Louis, MO

Patricia Thomas - Arlington, MA

Steve Wakefield - Chicago, ILAVAC gratefully acknowledges many friends and colleagues in government, industry, and community advocacy for their expertise and advice as we researched this report. We especially thank Mary Allen, Bob Belshe, Chris Collins, Jose Esparza, Pat Fast, Mark Harrington, Lisa Jacobs, Peggy Johnston, Wayne Koff, Derek Link, John McNeil, Gary Nabel, Mike Powell, Jane Silver, Debra Riggin Waugh, Wendy Wertheimer, and Joy Workman for their helpful comments.

AVAC takes no funding from government or industry. This publication was made possible by grants from the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR) and the Until There's A Cure Foundation. AVAC thanks AIDS Action Council, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Gill Foundation, the John M. Lloyd Foundation, the Royal S. Marks Foundation Fund, and many individual donors for the general operating and in-kind support that makes AVAC's advocacy possible.

Dedicated to

Paul Corser

Dr. Mary Lou Clements-Mann

Dr. Jonathan Mann

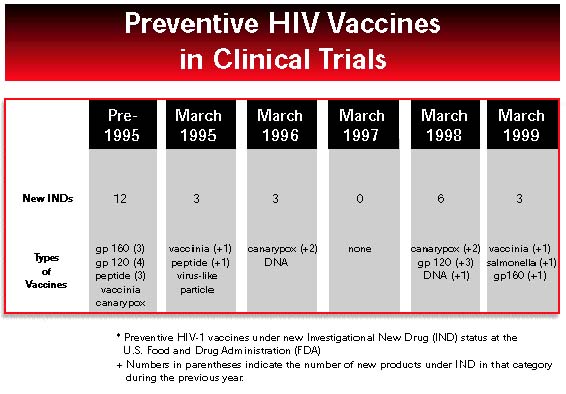

In May 1997, President Clinton set a national goal of developing an HIV vaccine within the next decade. This goal is laudable, but there is evidence that it may not be met. The development and testing process will be long, and the number of vaccine candidates in early clinical trials is falling, not rising. So far, only one product has entered large-scale efficacy testing. Although some promising new ideas are percolating in laboratories around the world, it might be years before these will be tested in humans.

We urge government, industry, and community to dedicate themselves to the development of a safe and effective HIV vaccine. If the goal for 2007 cannot be achieved, then we need to know what will be accomplished over the next eight years toward a vaccine that could bring the HIV pandemic under control. With 16,000 new HIV infections each day, the world can afford no delay. This report describes what each of these sectors has accomplished during the past year, and outlines what each can do to speed the search for a preventive vaccine.

Government is funding the basic research needed for a vaccine, and it is developing a structure to advance promising concepts and products. But US government agencies should expand their capability to research and develop new vaccines rapidly.

- Government must be bolder in coordinating its agencies’ agendas and must demonstrate far-sighted, results-oriented leadership and research plans.

- Government must increase the pace of research, by moving outside its basic science focus to strengthen product development and clinical research efforts.

- Government must facilitate community participation in research through more active support of trial site community advisory boards.

Industry has the expertise and infrastructure to bring a vaccine to the public. Some companies are investing more now than in years past. But too many companies are failing to treat this as their responsibility, largely because of scientific risk and uncertain profits.

- The world’s largest vaccine pharmaceutical companies must shoulder more of the risk involved in HIV vaccine discovery and development and must commit more dollars and expertise to the effort.

- Industry must take greater advantage of government funding initiatives and smaller company ventures to leverage vaccine development.

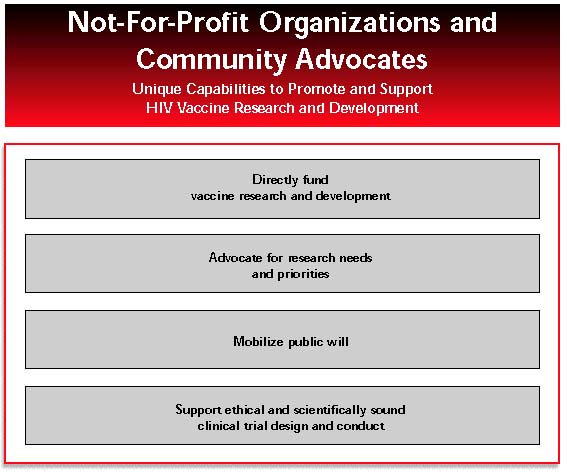

Not-for-profit organizations and community advocates are finally stepping up to the plate in the drive for an HIV vaccine, and they are beginning to realize their potential for public education and support of innovative research.

- Funders and advocates should do all they can to support not-for-profit organizations such as the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation that directly fund HIV vaccine research and development.

- The public can support initiatives such the tax credit for vaccine research recently introduced in the US Congress (House Resolution 1274).

- HIV treatment and prevention advocates must integrate support for HIV vaccine research and development into the AIDS research advocacy agenda.

- Not-for-profit AIDS organizations, public health organizations, and HIV prevention planning groups must seize responsibility and opportunities to mobilize the public about the priorities and potential results of biomedical research on vaccines.

- Trial site community advisory boards increasingly have a place at the table in planning research, but must live up to this responsibility with sustained, well-informed involvement.

Last year’s report of the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition (AVAC) opened with a photo of humankind’s first giant footsteps on the moon. This year, the AIDS vaccine program looks less like the soaring Apollo adventure than like the static orbit of Sputnik.

The missing element in the search for an HIV vaccine is urgency. Everything takes too long. As we said a year ago, without explicit goals and greater accountability, an effective HIV vaccine will not be available by 2007.

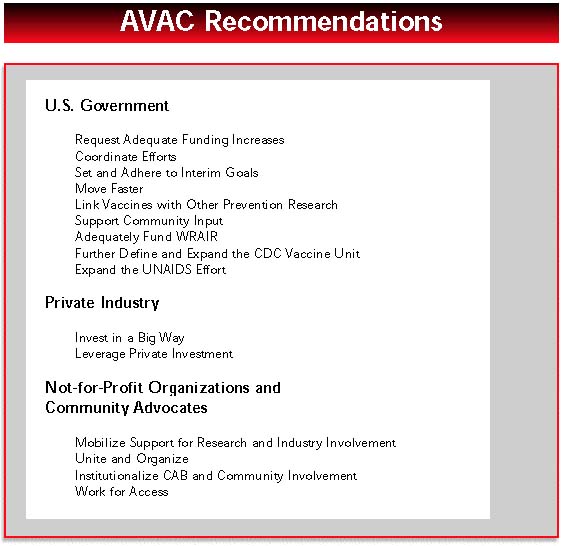

To boost the vaccine endeavor into higher orbit, AVAC has the following recommendations.

US Government

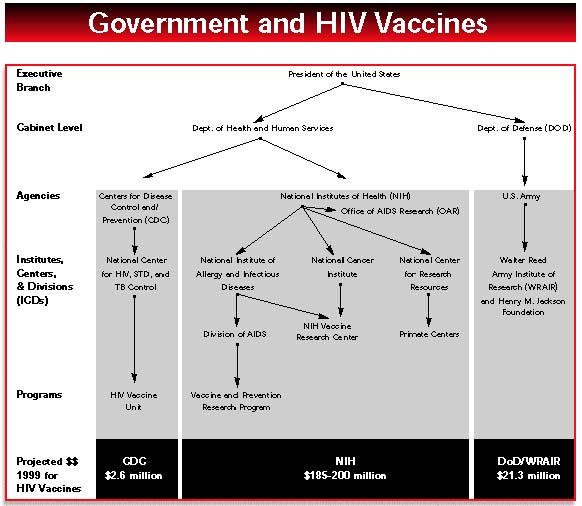

Request Adequate Funding Increases- For FY 2000, President Clinton requested a meager 2.1% increase for the National Institutes of Health, a 1% increase for the Centers for Disease Control, and level funding, after a 40% decrease in FY 1999, for the Department of Defense AIDS research program. These funding requests from the White House reflect crass political budget maneuvering, and belittle the hard work done by these three US government agencies. The White House must request adequate funding increases for the US government agencies that conduct biomedical research.

Coordinate Efforts

The time has come for the National Institutes of Health, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the US Agency for International Development to formulate compatible plans and make them clear to the rest of the world. There is mid-level communication among these US government agencies; what’s needed is leadership strong enough to harness the abilities of all four agencies. These agencies should present a coordinated effort wherever they are supporting clinical trials.

Set and Adhere to Interim Goals

In last year’s report, we said, “Agencies funded to conduct HIV vaccine research and development should establish clearer plans and goals to expand the HIV vaccine pipeline,” and “the US government must be clear about who should take responsibility and accountability to achieve these goals.” We listed five interim goals that would indicate a widening of the product pipeline; this year we have added a sixth:

- increase the annual number of targeted research projects that are applicable to new and improved vaccine concepts;

- increase the annual number of vaccine concepts evaluated in primate models;

- increase the annual number of vaccine products evaluated in phase 1 trials;

- increase the number of industry partners involved in developing HIV vaccines;

- increase the annual number of products developed that can move into phase 2, proof-of-concept, or phase 3 efficacy trials and

- (added interim goal): increase the number of domestic and international trial sites with the capacity to participate in phase 3 testing of HIV vaccines.

We challenge the government agencies involved in HIV vaccine research and development to set clear, measurable goals for each of these six areas. These goals should be stated, and progress toward them reported, by May 2000 when the countdown reaches “seven years and counting.” (see letter, page 10)

National Institutes of Health

Move Faster- In 1996, in our Agenda for Action for an HIV Vaccine, AVAC’s first key recommendation was that “NIH leadership must be accountable for effectively advancing efforts in AIDS vaccine research.” We recommended that, “If NIH does not take up this critically important responsibility within a fixed period of time, authority and funds for the task should be placed elsewhere.’”

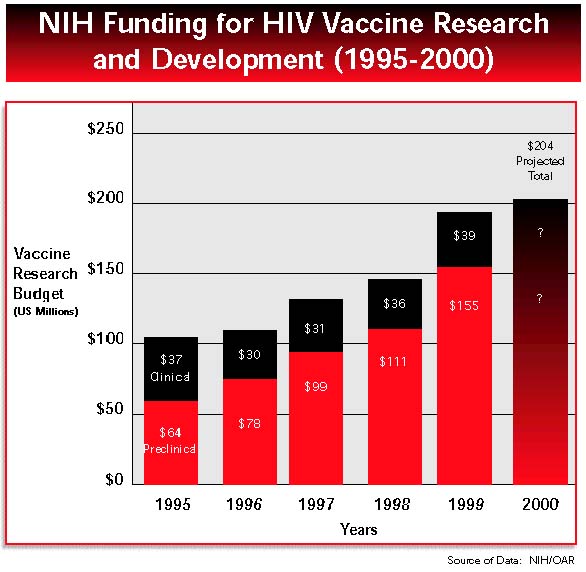

Since 1996, we have witnessed a great deal more attention and government money in the vaccine effort as well as well-qualified committed leaders finally in place. During the past year, of the NIH $1.8 billion dedicated to AIDS research, $194 million (11%) was allocated for HIV vaccine research. During the past year, NIH veteran Peggy Johnston was appointed as Assistant Director for AIDS Vaccines at NIAID and Associate Director of Vaccines within the Division of AIDS (DAIDS), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Virologist and AIDS Vaccine Research Committee member Neal Nathanson was appointed as Office of AIDS Research Director, and gene therapy researcher Gary Nabel as Director of the NIH Vaccine Research Center.

These individuals have taken on important new responsibilities, in many cases they have been provided with additional funds, and obviously they will need time to have an impact. Opportunities for accelerating the pace of vaccine development can be seized now, as shown by the examples below.

- In 1997, NIAID created a new Innovation Grants program with minimal red tape and got it up and running in just a few months, which is record time. Now, two years later, that program has begun to look like any other: it is reviewed by sound standing study sections along with other grants, and more awards are going to the same kinds of basic immunology and pathogenesis projects that older programs also fund. The number of applications is declining, and more and more awards are going to the same researchers who have always received NIAID support, rather than expanding the research pool. Johnston, Nathanson, Nabel, and members of the AIDS Vaccine Research Committee should publicize this program and actively seek new applicants.

- One large-scale comparative primate study of HIV vaccines is beginning soon. This will be the second large primate study of HIV vaccines conducted by NIH; the first has yet to publish data. NIAID and the National Center for Research Resources should move these studies forward and initiate additional comparative development work in primates immediately. To that end, NIAID should increase product development funding to generate vaccine candidates that are optimized for comparative primate studies.

- The HIV Vaccine Design and Development Program has not yet accepted applications or funded a single team. DAIDS management has been presenting and describing this program as a key element of their vaccine program for the past two years. NIAID staff should take the opportunity to ensure that this program attracts appropriate interest and moves the development process forward in ways that the old programs could not.

- NIH has finally hired the University of Michigan’s Gary Nabel as director of the much-touted Vaccine Research Center (VRC). The building cornerstone will be laid any day, and the next challenge is to make VRC a true center of excellence for HIV vaccine research and development. NIH should, as promised, provide Nabel with the authority and resources needed to staff the center with the best and brightest vaccine scientists, whether they are selected from within NIH or brought in from outside NIH.

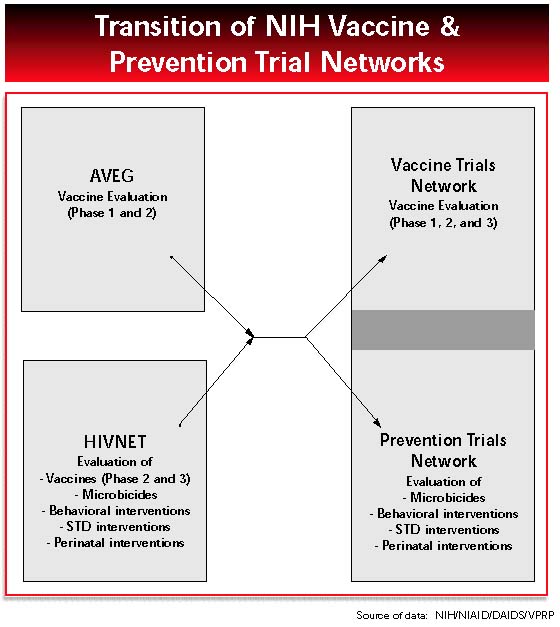

- NIAID should increase the number of clinical trials and ensure that the new clinical trial networks are adequate to evaluate candidate vaccines at all stages, from initial safety studies through large-scale trials needed for licensure. So far, countless hours of investigator time and attention have been consumed by replacing a phase 1 and 2 network for vaccines (AIDS Vaccine Evaluation Group) and a phase 3 trials network for vaccines and prevention (HIV Network for Prevention Trials), with the new HIV Vaccine Trials Network and HIV Prevention Trials Network. This has distracted NIAID staff and extramural scientists from the real task at hand conducting trials that will move an array of vaccine candidates forward. Another cause for concern is the capability of the new HIV Vaccine Trials Network to launch a phase 3 vaccine trial in 2000.

Link Vaccines With Other Prevention Research

NIAID’s Division of AIDS should be very careful as it separates vaccine research from research on other prevention interventions and hands responsibility of clinical testing to independent investigators. In principle, this reorganization and delegation could increase the focus and scientific viability of each program. However, giving more control to outside researchers will not by itself improve the pipeline of vaccine development. In addition, the reorganization threatens important and hard-won gains, such as community involvement and education. Coordination and synergy between vaccine and prevention research will be needed. This is more likely if some trial sites participate in both networks and if they have the flexibility to test the most scientifically promising strategies whether these are vaccines or other interventions. Johnston and her team should be active in their management of these networks, mandating coordination of infrastructure and research as well as making sure that research findings are promptly reported and shared.

Support Community Input

Clinical trial sites, whether funded by government or industry, have an obligation to develop guidelines for local community input into the planning and conduct of research. Community must be involved before, not after, research plans are set. Community Advisory Boards (CABs) should be supported more actively as one way to facilitate community involvement.

US Department of Defense

Adequately Fund WRAIR

The HIV vaccine program of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) has considerable strengths in applied research, relationships with companies and countries, and coherent long-term strategizing for product development. Unfortunately, this year WRAIR suffered two setbacks: a drop in funding, and the prospect of having a larger-than-expected efficacy trial in Thailand due to the laudable success of prevention programs among potential vaccine cohorts. Even well-made battle plans do not always succeed. WRAIR needs alternate locations for its research as well as sufficient funds to prepare and support them; yet, it has consistently been under-budgeted, depending on congressional whim for adequate support.

The US Department of Defense must budget and support the WRAIR AIDS research program at realistic, progressive levels that are flexible enough to accommodate unforeseen developments. The few million dollars this would require are minuscule compared to the damage inflicted by AIDS in locations where the United States has defense interests or in relation to the total defense budget.

The WRAIR HIV vaccine program has an advantage over other US government agencies in that it is targeted in its approach and is not hindered by multiple oversight and review committees. Still, WRAIR could increase public input and scientific review by researchers in industry and outside the Department of Defense.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Further Define and Expand the CDC Vaccine Unit

In 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established an HIV Vaccine Unit within its National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention. Its budget is small: $2.6 million out of the agency’s $2.5 billion total (0.1%). Yet CDC has longstanding international and US contacts and capability to conduct virology studies and preparedness studies in several potential trial sites. The agency can also bring expertise to risk reduction and informed consent procedures in phase 3 trials.

We challenge CDC to fulfill its potential by defining its plans and setting clear and measurable goals for coordinating its activities with better funded domestic and international players, especially NIH, WRAIR, and companies whose products may be suitable for testing in sites prepared by CDC. Funding should be increased as needed to implement these plans.

International Funding

Expand the UNAIDS Effort

Designing and testing vaccines will have to be a cooperative international effort. In African, Asian, Latin American, and Caribbean countries where HIV vaccine trials might be held, vaccine manufacturers and sponsoring companies need to work with local governments, researchers, and community advocates to prepare for useful, ethical, and cost-effective research. The Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has played a valuable role in supporting countries in building capacity to evaluate the scientific and ethical merits of potential HIV vaccine trials. Unlike the pharmaceutical companies and Western governments seeking to sponsor HIV vaccine trials, UNAIDS can have a neutral advisory role regarding HIV vaccine research.

Governments should increase funding for UNAIDS vaccine efforts. UNAIDS should leverage additional resources and expertise from partner agencies and countries to expand technical assistance to countries preparing for HIV vaccine trials.

Private Industry

Invest in a Big Way

Industry’s investment in preventive HIV vaccine development remains inadequate. Most companies that have performed significant vaccine work have benefited from direct or indirect government support. Although government-industry partnerships are valuable and should be encouraged, more reciprocity should be involved. Companies can shoulder more of the risk involved in HIV vaccine research and development, and most should be willing to invest more of their own resources in an endeavor of such public health significance.

Leverage Private Investment

Attempts to “leverage” private investment have taken several forms. Government agencies such as NIH have provided research resources, including viral isolates, access to primate centers, and infrastructure for clinical trials. More recently, NIH and the not-for-profit International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) have established programs that provide direct financial support for private companies conducting HIV vaccine research. IAVI has chosen two teams, and NIAID plans to choose teams this summer. On the legislative side, US Representatives Nancy Pelosi and Charles Rangel recently introduced legislation (House Resolution 1274) to provide a tax credit for new research on HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis vaccines. These initiatives should be supported by advocates and industry more aggressively.

The US government and foundations have come forward with a variety of measures to address the financial costs, risks, and “opportunity costs” of researching and developing HIV vaccines. Large and small pharmaceutical companies should stop making excuses, take advantage of the incentives, and pitch in to conquer this problem.

Industry must take advantage of initial investment by private foundations or government to determine feasibility of new approaches to HIV vaccines at minimal risk and cost to companies. Whereas investment by large pharmaceutical companies such as Pasteur Merieux Connaught and Merck is laudable, corporate management should appreciate the magnitude of this project and its potential contribution. Additional industry investment could shave years off the vaccine development process, save many lives, and accelerate research progress and profits.

Not-for-Profit Organizations and Community Advocates

Mobilize Support for Research and Industry Involvement

Advocates for HIV treatment and prevention must integrate HIV vaccine research into the AIDS agenda. Not-for-profit AIDS and public health organizations should seize responsibility and opportunities to mobilize the public about the priorities and potential results of biomedical research. All should support direct funding of HIV vaccine research and development by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, the American Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation. All should support initiatives such as vaccine research tax incentive legislation recently introduced in the US Congress (House Resolution 1274) and a vaccine purchase fund currently under consideration at the World Bank.Unite and Organize

Advocates for AIDS research, women’s health, health and rights of vulnerable communities, and international health should also unite to advocate for HIV vaccine research. The major AIDS organizations, AIDS media, and CDC-sponsored prevention planning groups ought to integrate support for vaccine research into their policy analysis, education, and communications.

Institutionalize CAB and Community Involvement

Local and national community advisory boards (CABs) can secure more support and resources from trial sites and from the new vaccine and prevention trial leadership. Local CABs, assisted by program staff and researchers, should develop standards and expectations for local activity. On a national level, clearer processes for CAB dialogue and decision-making would benefit CABs and the government agencies and private companies that work with them.

Work for Access

An HIV vaccine cannot save lives unless people have access to it. Advocates can mobilize in advance to make preventive vaccines for HIV and other diseases widely available to economically disadvantaged populations and individuals. Advocates can work to understand and address access issues, such as tiered pricing, product liability, intellectual property rights, and international product licensing laws.

US government agencies must coordinate their efforts, make explicit plans with clear milestones, and speed the movement of products through the vaccine pipeline.

In the world of HIV vaccine research, 1998 was a year when the US government made strides in articulating its mission but moved slowly to turn promises into actual programs at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Walter Reed Army Institute for Research (WRAIR), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Overall, NIH, WRAIR, and CDC “talked the talk” as never before. The HIV vaccine research agenda became less isolationist and more international, a step toward claiming US leadership in global disease prevention. Official support for phase 3 trials increased. Calls came for stronger product development efforts, expanded primate studies, greater collaboration with industry, and broader clinical testing of new HIV vaccine products. Despite the talk, the US government is just beginning to “walk the walk.” Funding for HIV vaccine research at NIH, WRAIR, and CDC must increase. Leaders at NIH, WRAIR, and CDC must act decisively and quickly to move the science forward. Some examples of what needs to change are presented below.

- The US government has yet to launch a phase 3 vaccine study of its own; instead, it is retooling its system for conducting such tests. The new vaccine trials network, funded at $14 million in its first year, is not budgeted adequately to mount a phase 3 trial in 2000. NIH, Pasteur Merieux Connaught, and VaxGen seem unable to agree on the supply of products for testing. Top NIH officials must do everything possible to advance NIH’s first phase 3 vaccine trial.

- In 1998, NIH launched only four new phase 1 safety trials of HIV vaccine candidates, down from six new trials in 1997. The total number of volunteers in NIH-sponsored trials also declined. NIH leaders must work to reverse these declines.

- Large comparative primate studies of vaccines could provide important data about vaccine concepts; however, only one such study is currently planned, and serious challenges exist in creating and optimizing products for this study. NIH officials must be bold in soliciting applications from researchers who are ready to move their ideas into primate testing.

- The preclinical portion of the vaccine pipeline is disturbingly empty, and there is little evidence that it will soon be filled. It is imperative that NIH augment its programs to galvanize research on new vaccine strategies, both in academia and in the private sector.

In 1998, NIH announced several exciting new initiatives to facilitate product development, including new production contracts, vaccine development teams, and one large comparative primate study. Implementation of these initiatives depends on strong industry buy-in and participation, researcher enthusiasm, sustained government funding, and willingness of NIH officials to take risks and do things differently.

Within government agencies, a chorus of voices now calls for a greater US role in the development of HIV vaccines for global use. WRAIR continued in 1999 to back phase 1 and 2 clinical trials in Thailand; NIH supported a much-anticipated phase 1 trial in Uganda and expects to launch another study in the Caribbean before the end of the year. International trial sites were encouraged to apply for NIH’s new networks for testing vaccines and other preventive measures, and several NIH program announcements were revised to enable non-US institutions to apply for funding.

These are positive developments. At the same time, NIH’s new clinical trials networks are only moderately funded, and the new HIV Vaccine Trial Network is less likely than its predecessor, the HIV Network for Prevention Trials, to have a strong international component. WRAIR has found that efficacy trials in Thailand may become impractical and may not have the resources needed to establish an alternate trial site.

NIH gained new leadership by recruiting Peggy Johnston, a prominent spokesperson for the global vaccine cause, to lead its HIV vaccine research and development programs. The Office of AIDS Research is now led by Neal Nathanson, a distinguished researcher and champion of vaccines. The NIH Vaccine Research Center just hired Gary Nabel from the University of Michigan as its new director. President Clinton continues to verbally promote a strong HIV vaccine research program as one of his legacies. These leaders must move bureaucratic mountains if they are to succeed. Boldness is needed to identify programs that do not work, create new programs that do, and ensure that spending addresses current scientific priorities and opportunities. Political leadership is needed to mobilize public support for HIV vaccine research and to promote acceptance of an HIV vaccine when one is finally available.

NIH must act with greater urgency to widen and fill the HIV vaccine pipeline.

The National Institutes of Health is the world’s largest and richest government medical research institution. NIH has a $15.6 billion budget for the current fiscal year, and there is more construction under way on its 318-acre campus than in many small cities. In the small pond of HIV vaccine research, NIH is the multi-tentacled octopus, lending an arm of support to nearly every vaccine approach. Last year, it awarded contracts and grants worth $148 million to public and private-sector investigators working on HIV vaccines. It is no surprise that NIH support is seen by most vaccine developers as crucial in bringing any product to fruition. Funding for NIH must continue to increase.

Managing NIH Money

For fiscal year 1999, the big picture is that NIH’s total AIDS budget is $1.8 billion. Of this, $194.1 million has been earmarked for HIV vaccine research, an increase of $46 million over the previous year. NIH leaders deserve credit for increasing overall funds for HIV vaccine research. NIH leaders also deserve credit for their efforts to allocate and coordinate the vaccine budget across institutes. This is work in progress; more can be done.

Among NIH institutes, NIAID is the major player, receiving more than 75 percent of NIH HIV vaccine research dollars in FY 1998. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) each receive about 5 percent, or about $8 million. NCI vaccine spending focuses mainly on large intramural contracts, with a few good researchers conducting innovative work on the NIH campus. NCRR dispenses most of its funding to Regional Primate Research Centers, where primate colonies are maintained for HIV vaccine research.

The NIH Office of AIDS Research (OAR) is another major player in the HIV vaccine effort. The role of the OAR is to coordinate the scientific, budgetary, legislative, and policy elements of NIH AIDS research. The OAR is responsible for developing an annual plan for all AIDS research at NIH, and determines the distribution of AIDS research funding to the NIH institutes and centers based on the objectives and priorities of the annual plan.

The OAR also administers an emergency discretionary fund of approximately $10 million each year. In 1998, most of this discretionary fund was used to support vaccine Innovation Grants, and for research to prepare for conduct of international vaccine clinical trials. In FY 1999, the OAR, through its funding distribution to NIAID and NCI, provided $16.5 million to support the operations and activities of the new NIH Vaccine Research Center (VRC).

Leadership at NIH

NIH’s readiness to launch an all-out HIV vaccine effort has been increased by the recruitment of new administrators. AVAC has often criticized NIH and the US vaccine effort in general for lacking leadership, clear lines of responsibility, and accountability. This is changing. In 1998, NIH created one new leadership position and filled three top slots with people who are generally seen as excellent choices.

In June 1998, Neal Nathanson succeeded William Paul as Director of the Office of AIDS Research at NIH. A long-time virologist who had been on the AIDS Vaccine Research Committee since its inception in 1997, Nathanson arrived well versed in the issues and complexities of HIV vaccine research. So far, his focus includes bridging the gap that separates preclinical development from human testing, ensuring that clinical trial networks are firmly in place when NIH eventually decides to conduct an efficacy trial and using primate models to shed light on correlates of immunity for HIV and other vaccines.

NIH veteran Margaret “Peggy” Johnston returned to NIH in September, having spent two and a half years as founding scientific director of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative. Johnston returned to fill a newly created position, NIAID Assistant Director for AIDS Vaccines, and an old one in DAIDS, Associate Director for Vaccine and Prevention Research.

In March 1999, Gary Nabel, the new director for the NIH Vaccine Research Center was finally hired. Bulldozers have broken ground for this new center, and a cornerstone for the new center is due to be laid any day now. Now begins the task of bringing in the scientific and vaccine development expertise that can make VRC a driving force in HIV vaccine development.

A major question, of course, is whether Johnston, Nathanson, and Nabel can work together to deliver a more coherent and accountable approach to vaccines. These three leaders already have a collegial working commitment to the HIV vaccine effort, but they face major challenges. Inertia in the NIH system always endangers efforts to alter programs or move with more dispatch. Staff vacancies at DAIDS, and the need to begin staffing the Vaccine Research Center, provide opportunities for good new hires. Inevitably, this also will take time away from the task of developing an HIV vaccine.

The Structure of NIAID Extramural Funding

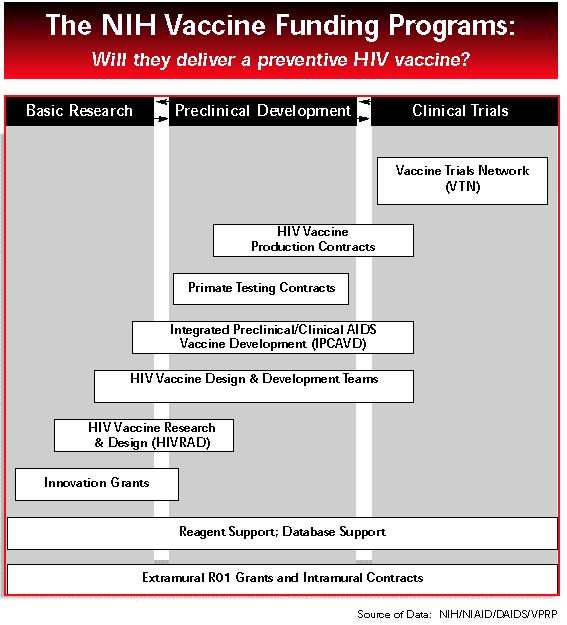

In 1998, NIAID began restructuring and renaming its extramural funding programs for vaccines and announced several new initiatives to increase funding for HIV vaccine research. The goal is to create a well-funded and seamless continuum of funding that will carry promising vaccine concepts “from the investigator’s brain to the volunteer’s arm,” as one optimistic DAIDS scientist phrased it, with few glitches and delays.

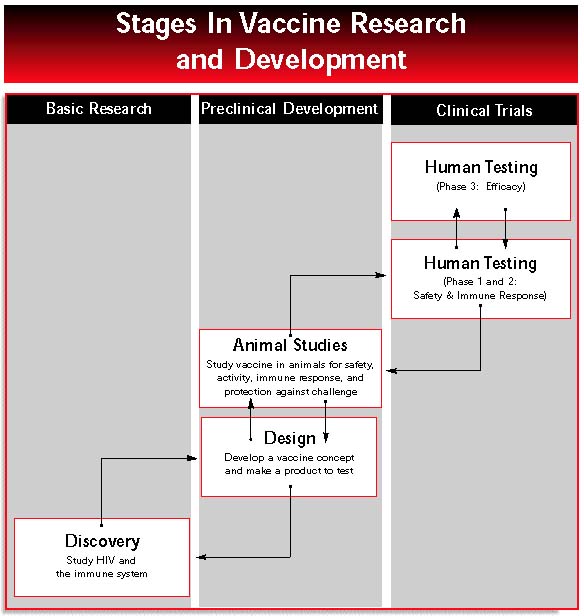

As envisioned by NIAID, this system would function like a salmon ladder: lots of embryonic concepts leaping the lowest rungs and obtaining seed money for ideas, with several of the most successful competitors reaching higher levels of funding that lead to evaluation in clinical trials (see diagram, p 22). This tidy vision incorporates many existing and renamed programs. Whether this vision will coalesce into a system that can produce rapid results remains to be proven.

Grant Review and Renewal

In 1996, the Levine Report (formally titled the Report of the NIH AIDS Research Program Evaluation Task Force, chaired by Arnold Levine) recommended that NIH establish a separate study section to review applications for research on vaccines against HIV and other pathogens. This recommendation was motivated by complaints from vaccine researchers, who often felt at a competitive disadvantage in traditional study sections where basic science got more respect. In 1998, this led to the reorganization of ten study sections (as NIH review committees are known) into nine: eight focused on basic science related to HIV and one specifically focused on vaccine development. The new study section considers only applied vaccine science and reviews proposals for developing vaccines for HIV and other infectious diseases. The first meeting of this study section, held in November 1998, reviewed more than 50 vaccine applications, including about two dozen HIV vaccine applications from the Innovation Grants program, and a few HIV vaccine applications from the Small Business Innovation Research program.During the past year, ongoing vaccine research endeavors received strong continued support. In 1998, NIAID, which carries most of the long-term contracts and grants for HIV vaccine research, changed its funding formulas in two ways that benefit researchers with multi-year awards. Consequently, the amount in a 1998 grant renewal received by an investigator is now closer to the original approved amount than it was in past years.

The Start of the Funding Continuum: Preclinical Research Grants

Innovation Grants

As one of four NIH funding programs for preclinical HIV vaccine research, innovation grants were initiated in 1997 by the AIDS Vaccine Research Committee (AVRC) and then newly appointed DAIDS Deputy Director, Carole Heilman. The purpose was to draw new researchers into the HIV vaccine field and increase the number of promising concepts entering the research pipeline.Ideally, a large number of vaccine researchers will be funded by innovation grants, will generate preliminary data about their vaccine concept, and then will move their vaccine research successfully into primate studies and development. It is too early to tell whether the first innovation grants have generated new candidate vaccines, but there is evidence that the program is attracting smaller numbers of new investigators.

The Innovation Grants program got started with a bang. Dozens of new researchers were funded for important areas of research such as HIV envelope structure, HIV antigen processing, and improved animal models for HIV vaccine research. New investigators with no HIV vaccine experience were encouraged to apply, the application process was simpler than for most NIAID grants, and the funding amounts were small, basically seed money, usually no more than $150,000 per year for a maximum of two years.

About 150 applications were received for the first round of funding in 1997, and 49 of them were awarded two-year grants totaling $13.2 million. This was the first extramural NIAID grant for 28 of the successful applicants, suggesting that the program was bringing new talent into the HIV vaccine field. The program has been shrinking ever since. The number of proposals fell to about 100 for the second round of funding, and 39 two-year awards were made for a total of $8.7 million. Another $2.3 million went to extend the grants of researchers who had secured one year of support in the first round. The reviews for these rounds were conducted by a special emphasis panel convened by NIAID.

The third round of funding, announced in May 1998, garnered about 50 proposals. More importantly, the innovation grants became “business as usual” for NIAID. Although the program announcement again asked for “projects of an exploratory nature to generate preliminary data for further studies” and focused applicants on two areas of inquiry, it embraced for the first time “applications targeting any scientific areas related to AIDS vaccine research”, broadening its reach to more areas of basic immunology and pathogenesis. The application cycle was synchronized with the normal NIAID funding schedule, and proposals are now being evaluated by the Center for Scientific Review instead of by a special committee. About half of the 50 applications were reviewed by the new vaccine study section and half by review sections focusing on immunology and pathogenesis of HIV infection, and molecular and cellular biology of HIV.

The drop in number of applications is striking; from 150 to 100 to 50 in less than one year. Although it is possible that all the investigators with bright new ideas were funded in the first two rounds, it may also be that members of the AVRC are not “beating the drum” or being as targeted as they were when the program was new. If there is a shortage of applicants who are committed to HIV vaccine work, the Innovation Grants program could become merely a novel source of support for basic science that has nothing to do with the vaccine effort. The fact that NIH staff shunted more than half of the third-round proposals to basic science study sections hints at this.

To attract high numbers of quality applications, the administrators of this grant program could focus more attention on scientific questions important to vaccine research, while keeping the grant application and award processes simple, frequent, and quick. Johnston, Nathanson, Nabel, and the leaders of AVRC can play a key role by publicizing this program and encouraging new applicants.

The ultimate proof of the innovation grants will be if one or more of them spawns testable candidate vaccines. An interim measure of success will come when the program’s alumni apply for standard investigator-initiated grants or become part of multi-investigator projects. Published results from the innovation grants are beginning to appear, but it is still too early to judge how many grantees will successfully climb to the next stages of the NIH funding ladder.

HIV Research and Design Grants

The goal of the HIV research and design (HIVRAD) grants is to support development of HIV vaccine concepts into products. They are intended to be large enough (in the range of $2 million per year for five years) to fund all of the applied immunology, virology, animal models, and molecular biology research needed to demonstrate a vaccine concept’s potential for antigen expression, immunogenicity, and development for human testing. Proposals for HIVRAD funding may be from individual researchers or from large groups of investigators; in group applications, foreign institutions are eligible to apply.The early part of the HIV vaccine development process depends on the quality of investigators and projects applying for HIVRAD funding as well as the number and monetary amount of HIVRAD grants. In March 1999, NIH received only eight proposals for HIVRAD funding. With more than 100 vaccine research projects already funded by the Innovation Grants program and an enormous potential to combine different fields of expertise into exciting vaccine design applications, more is needed from NIH to solicit HIVRAD applications. NIH leaders and administrators should do more to encourage new teams of vaccinologists, immunologists, structural biochemists, gene therapy researchers, primate researchers, and others to advance their concepts into this part of the development pipeline.

HIV Vaccine Design and Development Teams

The HIV Vaccine Design and Development Teams are designed to promote a development-oriented approach to vaccines, from basic research through phase 1 and 2 clinical testing, by funding teams of researchers for long-term coordinated projects. This program was developed from recommendations during the past three years from NIH staff, from the 1996 Levine panel, and from a 1998 AVRC meeting, all urging NIH to consider funding a small number of extramural centers of excellence devoted to HIV vaccine research.In February 1999, NIH issued a request for proposals from academic-industry researchers who want to “augment the product pipeline” by developing new vaccine candidates that might be suitable for large-scale testing. NIH is now willing to fund as many as five teams of academic and corporate researchers, for up to five years at a total level of about $10 million per year. The deadline for proposals is July 2, 1999.

Integrated Preclinical/Clinical AIDS Vaccine Development Grants

The Integrated Preclinical/Clinical AIDS Vaccine Development (IPCAVD) program is meant to encourage academic-industry collaborations that will move vaccines through the final preclinical stages and into early clinical trials, with a maximum award of $1 million per year.The IPCAVD program got off to a weak start in April 1997, when it was announced as the successor to what had been called the National Cooperative Vaccine Development Groups program. More than $10 million in funding went to 10 projects in 1997, but overall, basic scientists with vaccine concepts nowhere near clinical evaluation garnered most of the first-round funding. In July 1998, NIAID rewrote the program announcement so that human testing is a required part of the proposed work and specified that testing plans must be realistic, not “pie in the sky.” Another change invites international institutions to participate in IPCAVD consortia. It is too early to assess whether this program will develop more products for clinical trials.

NIH Intramural Vaccine Research Center

An additional NIH initiative to feed more products into the HIV vaccine pipeline is the NIH Vaccine Research Center, announced by President Clinton in May 1997 as part of his plan for developing an HIV vaccine within 10 years. In 1998, ground was broken for the new VRC building and a cornerstone is due to be laid in May 1999. The 18-month search for a VRC director was extensive and, given the limited number of eligible candidates, exhaustive. In March 1999, University of Michigan gene therapy researcher Gary Nabel was named Director of VRC. In April 1999, a strategic planning session for VRC was organized with the participation of outside researchers and advocates. Efforts to staff the center are reportedly under way, and this will be a time-consuming process. Nabel’s challenge is to recruit the very best of intramural and extramural researchers and to ensure that the VRC team has expertise not only in basic science, but also in bringing products to the marketplace.The Next Step in the Funding Continuum; Applied Preclinical Research Contracts

Primate Testing Contracts

Although many are skeptical about the practical value of testing HIV vaccines in small animals and in animals more closely related to humans, such as non-human primates, many researchers believe that strong immune response or efficacy demonstrated by a vaccine in primates could indicate that vaccine’s effect in humans. However, comparisons of different HIV vaccine designs in primates have been limited. Different researchers use different species of primate, different vaccine antigens and designs, different challenge viruses, and non-standard research protocols. Not surprisingly, a product that protects in one model sometimes fails utterly in another, and it is difficult to make sense of conflicting results. NIAID is now trying to standardize these models so that study results will be more comparable and useful to basic scientists, industry executives, and others who must decide whether experimental vaccines merit further testing.For the past year, immunologist Norman Letvin (the leading animal experimentalist on AVRC) and Alan Schultz, of DAIDS’ Preclinical Research Branch, have tried to build consensus about a standardized challenge system that would allow investigators around the world to generate comparable results. Last year, NIAID began planning a comparative test of at least five vaccines in approximately 100 macaques. After at least one company backed out of a commitment to supply their product, it was decided that four of the vaccine constructs would be live vectors and one would be an envelope protein to be tested solo and as a boost. As of March 1999, investigators remain divided over what challenge virus should be used in this experiment, but they hope to iron out their differences, begin the trial this summer, and generate results by March 2000.

This worthy effort is no substitute for clinical testing; the “best” vaccine in any primate model might not be the “best” vaccine in humans. Weak results in primates should not cause sponsors to abandon a vaccine candidate for evaluation in people. Any minimum level of protection in macaques might not translate into the same level of protection in humans. But large comparative primate studies can provide important data to compare and improve vaccine design and immune responses.

More needs to be done to implement a series of large comparative primate studies. The 1999 study is only the second one of its size ever planned. A year will have elapsed from the idea to implementation. NIH officials have an opportunity to do more in optimizing vaccine products for these studies and getting more trials started.

HIV Vaccine Production Contracts

The purpose of the HIV vaccine production contract initiative, according to a request for proposals released in October 1998, is to make batches of candidate vaccines for academic investigators or small companies to use in phase 1 and 2 clinical testing. Successful contractors will be on standby until they are needed. Although NIH officials will not say exactly how much funding they will devote to this initiative, or how many proposals they received for the February 1 deadline, they are reportedly optimistic about the number of proposals and their ability to fund contractors adequately. Awards will be announced in August 1999.The Final Step of a Funding Continuum; Restructured Clinical Research Networks

If NIAID’s funding ladder were in place and fully funded, more candidate vaccines would probably be in clinical trials. As it is, the dearth of products in clinical testing is a reminder that a coherent system is still under construction.

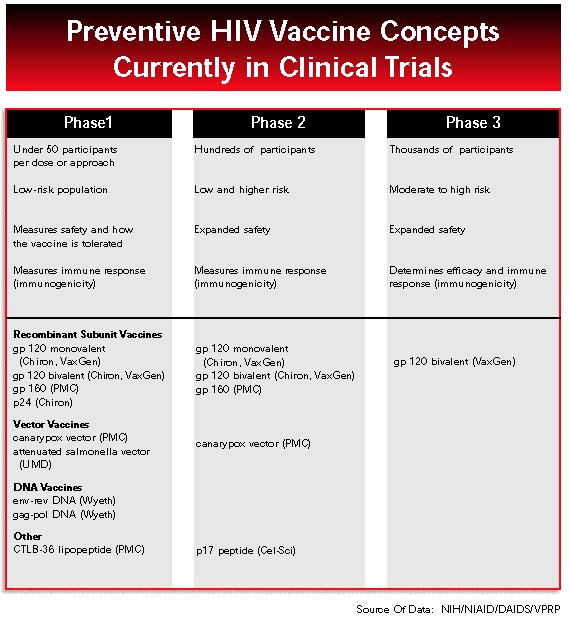

Early Clinical Trials

All told, NIH has 12 phase 1 and 2 studies under way, and these have enrolled a total of 990 current volunteers. More than half of these participants have received one of the Pasteur Merieux Connaught’s canarypox HIV vaccine vcp 205 (ALVAC) constructs. A recent phase 2 study, drawing from both HIVNET and AIDS Vaccine Evaluation Group cohorts, compares the safety and immunogenicity of three different avipox constructs in 100 volunteers. Most of the other 11 trials examine safety and immune responses of single vaccines at varying doses and with different accompanying adjuvants. Three of these are phase 1 studies of Wyeth-Lederle’s DNA vaccine, looking at increasing doses and various routes of administration. Two phase 1 AVEG trials are looking at immune responses of vaccine/adjuvant combinations, one where the adjuvant QS21 is given with two different VaxGen subunit vaccines, and another using Chiron’s p24 vaccine with the adjuvant MF59.In January 1998, NIAID announced the start of phase 1 trials for three novel approaches to HIV vaccination. One of these trials stands out because it is the first time that NIAID has sponsored clinical testing for a vaccine not owned by a company. This oral vaccine, which uses a weakened salmonella vector to deliver a gene for HIV envelope protein, was developed at the University of Maryland. Its testing was championed by Mary Lou Clements-Mann, who led the Johns Hopkins-based clinical study prior to her death in September. At this writing, 15 months later, accrual of 47 volunteers is still under way.

A second trial delivers ALVAC vCP205 first as an injection, then in topical doses to the mucosal surfaces of the nose, mouth, vagina, or rectum. This is NIAID’s first look at vaginal and nasal administration of an HIV vaccine, an important new area of research. Eighty-four volunteers have been enrolled at six AVEG sites.

A third study tests a chemical messenger called GM-CSF as an adjuvant with ALVAC vCP205. Only one type of adjuvant (alum) is currently used in approved vaccine products, and vaccine makers need more and better choices. Researchers at four AVEG sites have recruited 36 volunteers and immunized them; for the remainder of the 18-month study, the focus will be on determining whether GM-CSF enhances antibody and cellular responses to the vaccine.

Outside the United States, NIH has supported development of trial sites for nearly 10 years. NIH has used these trials to test various methods of preventing HIV transmission, including perinatal treatments, behavioral interventions, and microbicides. So far, one international HIV vaccine trial has been sponsored by NIH. Begun in February 1999 as the first preventive HIV vaccine trial in Africa, this phase 1 study in Uganda is evaluating ALVAC vCP205 in 40 low-risk volunteers.

First Efficacy Trial Begins:

In June 1998, the world’s first efficacy trial of an HIV vaccine was launched not by NIH but by VaxGen, a small company that now holds the rights to the gp120 vaccines originally made by Genentech. In June 1998, VaxGen began recruiting 5,000 high-risk volunteers, mostly men who have sex with men but also women at risk through sexual exposure, at 50 sites in the United States. In March 1999, a second efficacy trial began in Thailand, where 2,500 injecting drug users will be enrolled. Technical and financial support provided by NIH, CDC, and UNAIDS made it easier for VaxGen to recruit cohorts in Thailand and the United States. Now that these trials are under way, the fact that a private company has gone off the diving board first might make it easier for NIH to take the plunge with an efficacy trial of its own.NIAID’s Clinical Trial Restructuring

In October, requests for applications were published for “leadership groups” for an HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) and an HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN). In the past, phase 1 and 2 vaccine trials have been coordinated by the Division of AIDS and conducted at domestic sites that constitute the AIDS Vaccine Evaluation Group. A separate network of US and international contractors, the HIV Network for Prevention Trials (HIVNET), was designed to conduct phase 3 vaccine trials. HIVNET was never called on to implement a phase 3 vaccine study, but was used for vaccine preparedness work, one phase 2 trial, and a few small tests of other preventive measures such as topical microbicides, treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, behavioral interventions, and short-course therapy to reduce maternal-infant transmission.The new HVTN and HPTN structure will put all vaccine trials, phase 1 through phase 3, under a single HVTN umbrella, whereas the smaller parallel HPTN network tests behavioral interventions, microbicides, and other preventive strategies. Each network will be led by a group of principal investigators at a coordination and operations center (Core), a central laboratory, and a statistical and data management center.

The Vaccine Leadership Group (VLG), consisting of three or four academic researchers, will control a first-year budget of $12 million plus another $1.5 million in discretionary funds. These researchers will set the scientific agenda for all NIH-sponsored vaccine trials in the United States and abroad, will plan the transition from the current AVEG and HIVNET system, and will manage a network of approximately 10 trial sites selected by a competitive NIAID process. VLG will wield enormous power and will be self-governing, like the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG). The leadership group will have authority to reduce funding or even terminate poorly performing sites. This power may lead to new efficiency and speed, but the downside is that it could allow NIH leaders to sidestep responsibility for moving vaccines forward.

Not surprisingly, the leading contenders for VLG are AVEG and HIVNET leaders who first decided that the networks needed changing. They are expected to win this key contract, which will not be awarded until September 1999, and in fact may have no competitors. The HVTN clinical sites won’t be selected until March 2000.

As soon as the new HVTN is formed, it will be faced with the formidable challenge of negotiating, designing, and implementing a multi-arm phase 3 efficacy trial. The plan is to start a multi-arm efficacy study in mid- to late 2000 to test two or more vaccine concepts simultaneously. These will include a protein subunit vaccine, most likely made by VaxGen, and one of PMC’s avipox constructs used with one or more as yet undetermined boosts. Present thinking is that each arm would enroll 1,500 to 1,800 gay men and high-risk heterosexuals, recruited at domestic and international sites where Clade B viruses predominate. Despite the considerable authority vested in VLG, this phase 3 trial will not be settled until NIH decides on which products test and negotiates business agreements with companies for supply of the products needed for testing.

Finally, VLG must plan for community outreach and education and for establishing and supporting community advisory boards. This is essential for recruitment and retention of volunteers. The RFA for HVTN clinical sites, to be released soon, also must ensure that community participation and awareness efforts are funded adequately.

If the transition from the old clinical trials networks to the new HVTN goes without a hitch, if a phase 3 or intermediate-sized trial begins in 2000, and if there are no major barriers to enrollment, then the whole enterprise should take about 36 months to complete. This means that, by sometime in 2004, researchers will have an indication of which of these candidate vaccines looks best for further study, and they may have more insight into immune correlates of protection or the nature of viruses that infect vaccinated individuals.

The first planned HVTN efficacy trial may not be designed to generate, however, data that can be submitted to the Food and Drug Administration for marketing approval. The current plan is for a “screening” efficacy trial, not an “all-out” efficacy study such as the one that VaxGen launched in June 1998. Any vaccine that appeared protective in an NIH study almost certainly would not be on the market until after 2007. If a larger, definitive trial were conducted and efficacy demonstrated, several years could be shaved off this timeline.

Walter Reed Army Institute for Research

Vaccine research and development activities conducted by the Walter Reed Army Institute for Research augment and complement those at NIH. The Department of Defense should budget and support this program at realistic and progressive levels.

The Walter Reed Army Institute for Research (WRAIR) is the Department of Defense’s lead agency for infectious disease research, and it is the largest laboratory within the US Army Medical Research and Material Command. One of WRAIR’s central missions is to produce vaccines needed to keep American service personnel healthy no matter where they are deployed.

For FY 1998, WRAIR’s total budget for HIV/AIDS research was $40 million, thanks to $15 million that Congress added to the original budget request. About half of the total was spent on vaccine research, with 70 percent going for clinical trials and cohort development and 30 percent for preclinical research. In October 1998, military HIV vaccine research sustained a damaging hit when Congress appropriated only $21.3 million for FY 1999, a 47-percent reduction over the previous year.

This and other factors are forcing WRAIR to do more with less and to make some hard choices. For more than seven years, WRAIR and the government of Thailand have been preparing for an efficacy trial that would test at least two vaccine concepts: Chiron gp120 clade E+/-B in MF59 adjuvant alone, and in combination with PMC’s clade-E ALVAC, called vCP1521. Now the trial faces two major obstacles. On the corporate front, Chiron has greatly diminished, if not entirely dropped, its support for further development of gp120/MF59. PMC has been retooling its avipox construct, which could mean that vCP1521 may not be available for efficacy testing when the time comes.

The other problem is that successful condom campaigns have pushed incidence rates so low in long-standing Thai cohorts that they may be inappropriate for vaccine testing. WRAIR is now backing studies of several cohorts that might be suitable for large-scale vaccine trials in heterosexual volunteers, but results are not yet available.

With a phase 3 trial in Thailand in jeopardy, WRAIR is now looking at Uganda as an alternative site for testing vaccines in a large heterosexual cohort. At a February 1999 meeting in Uganda, representatives of PMC, VaxGen, and Wyeth visited a potential cohort and met with local scientists. They discussed the possible development of vaccines derived from A and D isolates collected by WRAIR (following a pattern set in Thailand, where WRAIR supplied isolates to companies) as well as clinical and laboratory infrastructure needed to conduct large field studies.

WRAIR’s dilemma is that Thailand now has the scientific infrastructure needed for a phase 3 study, thanks to years of work and substantial international investment, but the country may not have enough suitable volunteers. Uganda has abundant human capital, but its laboratories and clinics will need substantial investment to be ready for an efficacy trial. In Uganda and elsewhere, coordination among the US government agencies in their support for vaccine trials could dramatically speed the pace of trial preparations. To assist other countries in conducting HIV vaccine research, NIH, WRAIR, CDC, and USAID must work in alliance, drawing on the unique strengths of each agency and presenting a unified effort to the world.

On the domestic front, WRAIR is currently testing several products in phase 1 and 2 trials. These include Wyeth’s DNA vaccine (originally made by Apollon), PMC’s ALVAC construct called vCP205, and a PMC protein subunit, o-gp160 clade B. WRAIR is also negotiating for a domestic trial using Wyeth’s DNA vaccine as a prime with a PMC avipox boost.

WRAIR’s preclinical research program is small but diverse, so much so, in fact, that it may be spreading its resources too thin. Projects include novel vectors, collaborating with NIH researchers on modified vaccinia Ankara and with Duke University scientists on alphaviruses. Other in-house researchers continue to work on complex subunit proteins and antigen processing. Although WRAIR has a long history of successful partnerships with private industry, its financial resources are a limiting factor.

The HIV/AIDS research program at WRAIR is regularly reviewed by an internal scientific steering committee of the US Army Medical Research and Material Command. The program also has been reviewed by outside AIDS researchers every few years, with the last completed review in 1995. The WRAIR HIV vaccine program has an advantage over other US government agencies in that it is targeted in its approach and is not hindered by multiple oversight and review committees. Still, WRAIR could increase public input and scientific review by researchers in industry and outside the Department of Defense.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Despite the historic role of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in making AIDS a household word in the 1980s, the agency has never been a leader in HIV vaccine research. In fact, only in September 1998 did CDC establish an HIV Vaccine Unit within the National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention. The FY 1999 budget is the first to contain a line item for HIV vaccine research: $2.6 million out of the agency’s $2.5 billion total. (In comparison, NIH is expected to spend $194 million for HIV vaccine research in FY 1999.) Although it does not appear as a separate budget item, additional AIDS vaccine work is also carried out by virology laboratories in Atlanta and at field locations in Asia and Africa.

CDC is assisting VaxGen’s efficacy trial in the United States and reportedly will soon solicit proposals from large sites already participating in the study. CDC states that they will fund virology and social-behavioral studies on an estimated 1,000 volunteers at five or six collaborating sites. These studies will compare viruses responsible for infections among volunteers with incident infections in the community and will explore a long list of behavior questions related to participation and retention. CDC is also playing a substantial role in VaxGen’s phase 3 trial in Thailand, where its field station has long collaborated in studies of the injection drug user cohort now being used for VaxGen’s study. During the efficacy trial, CDC will consult on risk reduction counseling and informed consent issues as well as managing blood samples and scrutinizing participants who become infected. Laboratory studies conducted by CDC will augment those performed by hospitals in Thailand and by VaxGen.

In the preclinical arena, CDC has embarked on a long-term collaboration with Emory University and Yerkes Primate Center to develop a DNA clade A vaccine for Africa. This product, which is now being tested in primates, could conceivably be tested in Africa in another five years. Toward this end, CDC has begun setting up feasibility studies in five countries where it already has laboratories or ongoing collaborations. CDC is also working with the Association of Public Health Laboratories and NIH to develop a quick, inexpensive method for distinguishing people who have a positive antibody response due to vaccination from those who are infected with HIV.

Envisioning the Future

A successful US government effort to develop an HIV vaccine would see NIH, WRAIR, and CDC working together to increase industry involvement, support international clinical trial capacity, and move vaccine concepts into clinical evaluation. A successful US government effort would support a robust continuum of research, beginning with innovation grants and early proof-of-concept studies, continuing through preclinical and primate studies, and then moving through vaccine design and development, early clinical trials, vaccine production contracts, and efficacy trials.Of the US government agencies conducting HIV vaccine research, NIH has been the leader in overall funding and commitment, but NIH, WRAIR, and CDC are each needed in the HIV vaccine effort. All three agencies must work together more closely. In 1998, the leaders of NIH, WRAIR, and CDC began moving toward the kind of cooperation that will be needed to make their programs synergistic. During the coming year, they have many opportunities to strengthen these ties, fund new initiatives, and make good on their promises. If they succeed in doing this, real progress can be made toward a preventive HIV vaccine.

The world’s largest vaccine pharmaceutical companies must shoulder more of the risk involved in HIV vaccine development and commit more dollars and expertise to the effort. Industry must also take greater advantage of government funding initiatives and smaller company ventures to leverage vaccine development.

In 1996, AVAC interviewed researchers and leaders from 23 vaccine companies for a survey of industry investment in HIV vaccine research. At that time, only a few companies were investing seriously in HIV vaccine development. The three most frequently cited barriers to investment were:

- scientific feasibility;

- liability concerns; and

- opportunity costs of HIV vaccines relative to other products.

The top three solutions suggested by industry respondents were:

- direct contracting and funding from government;

- assistance in providing animal models for research; and

- tax deductions and credits for HIV vaccine research.

In May 1998, AVAC’s second published report stated that “during the past year, interest in HIV vaccine development by industry has remained minimal.” Today, in 1999, corporate investment in HIV vaccine development has improved, but still is not the forceful effort that the world needs.

In AVAC’s view, more must be done to galvanize pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. This includes direct government contracting, tax incentive legislation, more government investment in clinical trial infrastructure, better access to animal models, advances in basic science, and clear approval mechanisms in countries that could host phase 3 clinical trials. Just as important, of course, will be the willingness of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies to increase dramatically their own investment in HIV vaccine work.

When AVAC interviewed industry executives and scientists in 1996, many said that the greatest barrier to company investment was uncertainty about the science involved in making an HIV vaccine. Three years later, some knowledge gaps have been filled whereas other uncertainties persist. Yet these unknowns may never be overcome unless industry carries out the methodical development and empirical testing that it does best. Government expansion of basic science research into the human immune system and its interactions with HIV will not bridge all the gaps. There is no substitute for actually testing experimental vaccines and assessing their efficacy in clinical trials.

The Goal

What would a strong industry effort look like? If HIV vaccines were a top priority, each of the four major vaccine companies (SmithKline Beecham, Pasteur Merieux Connaught, Merck, and Wyeth) would have a strong investment in one or more vaccine technologies. Major companies without a strong history in vaccines, such as Glaxo-Wellcome, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Roche, would be competing for a stake in smaller biotechnology companies with HIV vaccine projects. Finally, the HIV vaccine efforts at the larger biotechnology companies, such as Chiron, would be on stronger footing in terms of external and internal support.

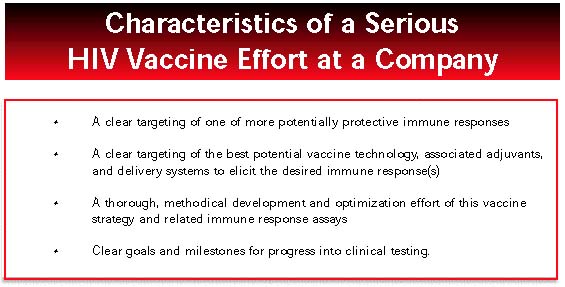

Each serious HIV vaccine effort would have certain characteristics:

- a clear targeting of one or more potentially protective immune responses;

- a clear targeting of the best potential vaccine technology, associated adjuvants, and delivery systems to elicit the desired immune response(s);

- a thorough, methodical development and optimization effort of this vaccine strategy and related immune response assays; and

- clear goals and milestones for progress into clinical testing.

Of the five major vaccine-producing companies, Merck, PMC, Wyeth, and Chiron have active HIV vaccine development programs. SmithKline Beecham has publicly announced only an adjuvant program.

Involvement Still Tentative

In 1998, industry followed prevailing scientific opinion toward vaccine strategies focusing on cytotoxic lymphocyte (CTL) responses, such as DNA vaccines and live vectors. In mid-year, Glaxo-Wellcome made a $20 million investment in PowderJect for use of its DNA gene gun technology; in early 1998, Wyeth acquired Apollon to gain its DNA-based vaccines. A new company, AlphaVax, was created by researchers working on a Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis (VEE) viral vector. And companies with multiple approaches under investigation, such as PMC, Wyeth, and Chiron, began emphasizing DNA and viral vectors over envelope subunit vaccines. Of all the companies, only VaxGen, with its phase 3 trial of a bivalent gp120, focused primarily on trying to elicit protective antibody responses.

Yet, despite rising interest in DNA and vector platforms, the major companies mostly engaged in “place-holding,” maintaining intellectual property rights and development potential for a few vaccine technologies but not seriously developing any of them. Although five companies work on DNA vaccines (Merck, PMC, Wyeth, Chiron, and Glaxo), none spent the kind of money on these products that companies typically invest in developing a new therapeutic drug. And, although at least seven companies have in-house programs to develop viral vector vaccines against HIV and other diseases (Merck, PMC, Wyeth, Chiron, Therion, AlphaVax, and Virus Research Institute), again it is unlikely that any invests more than $40 million per year on such a vector, except for PMC and its canarypox product.

Finally, SmithKline Beecham remains conspicuously absent from the HIV vaccine field. Although it is one of the largest vaccine producers in the world, the company said in an August 1998 letter to AVAC that it is not working on an HIV vaccine because it has no serious lead or clear direction to a candidate HIV vaccine.

Overall, company HIV vaccine programs are probably stronger than at the time of our 1996 industry report, and more investment will be forthcoming as greater evidence of scientific feasibility emerges. But bolder investment is needed now to generate that evidence. The following is a snapshot of current industry efforts during the past year.

Chiron

Founded in 1981, Chiron is one of the world’s leading biotechnology companies, employing more than 3,200 people and focused on biopharmaceuticals, blood testing, and vaccines. In 1998, for about $115.5 million, Chiron completed the acquisition of Behringwerke AG, the German human vaccines subsidiary of Hoescht AG that it began to acquire in 1996. The company manufactures vaccines in California and in Siena, Italy; a full range of adult and pediatric vaccines are marketed in Europe, and subsets are sold in the United States, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Revenues from Chiron’s vaccine business reached $177 million in 1998, with mid-year reports showing profits up 60 percent from the previous year.

Glaxo-WellcomeChiron Vaccines’ research and development program, under the strong leadership of Margaret Liu, is substantial and is now primarily focused on HIV and hepatitis C. Six different platform technologies are being explored in addition to work on adjuvants and novel delivery systems. Chiron Vaccines had some successes in 1998, with good results reported in late 1998 from its meningitis vaccine phase 2 trial, identification of a new hepatitis C viral receptor announced in October 1998, and work continuing on vaccines for cytomegalovirus, Haemophilus influenza B, meningococcus B and C, and Helicobacter pylori.

Chiron has a strong intention to remain in the HIV vaccine game. Chiron’s HIV vaccine effort is organized around a core HIV vaccine development team, with several supporting research groups: a DNA vaccine group, an adjuvant and delivery system group, and a gene therapy group that works on alphavirus vectors. Most of the work is preclinical, although Chiron’s gp120 is still being evaluated in US phase 1 and 2 trials in combination with MF59 adjuvant and various PMC avipox products. Chiron’s bivalent clade B/E gp120 vaccine is also being evaluated in various combinations in 380 volunteers in Thailand in a phase 1 and 2 trial.

Chiron’s current focus is to develop and optimize its DNA and alphavirus vector vaccines (using gag as the conserved antigen gene and some novel env structures) and then test these in combination with adjuvanted subunit protein in prime-boost regimens.

In 1997 and 1998, Glaxo-Wellcome, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, re-entered the vaccine arena. Glaxo and Wellcome each had vaccine divisions, but both were shut down before the merger. Still, in 1996, Glaxo had substantial in-house expertise in immunology that could be used toward vaccine development, patents on several viral and bacterial gene sequences, and at least one promising adjuvant called tucaresol, a co-stimulatory molecule with an effect on CD4 responses.

In 1996, an internal Glaxo Vaccine Project Group alerted Glaxo’s leadership to new opportunities in vaccines and recommended the creation of the Edward Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research in Compton, England. In an alliance signed in March 1997 with Cantab Pharmaceuticals in England, Glaxo built up its small in-house herpes vaccine effort. In 1998, Glaxo made a $20 million investment in PowderJect for use of a DNA gene gun technology and paid PowderJect $4 million to license a hepatitis B DNA vaccine.

With researchers at the Jenner Institute in Compton, plus immunology and new vaccine teams at Stevenage and Stockley Park, England, Glaxo has extensive resources to invest in product development. In 1996, Glaxo began to examine DNA vaccines as a means of protecting against diseases not amenable to antibody-mediated protection. Glaxo hopes to apply DNA vaccine technology to infectious disease prevention and to treatment of autoimmune and allergic diseases and cancer. It is unclear if Glaxo-Wellcome is interested in a strong HIV vaccine development program at this time.

Merck

Merck Vaccine Division, a unit of Merck & Co., Inc., is located in New Jersey and West Point, Pennsylvania. Overall, Merck & Co. has approximately 57,000 employees worldwide, has manufacturing facilities in 18 countries, and will invest close to $2.1 billion in research and development in 1999. Merck produces vaccines for hepatitis A and B, chickenpox, measles, mumps, rubella, and bacterial pneumonia. In 1998, Merck’s vaccine research program included clinical trials of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and a herpes papilloma virus vaccine.

Merck’s HIV vaccine program began in 1986, but remained at a low level of investment for years, with several vaccines leads that did not pan out and a much greater research energy focused on development of Crixivan and other HIV therapeutics. Two years ago, with Crixivan on the market, Merck began to publicly cite its vaccine effort as its major HIV-related research endeavor.

In 1997, Merck appointed Emilio Emini to lead an expanded vaccine program and turned its attention to DNA vaccines, deciding that a DNA vaccine to prevent HIV is promising enough to justify substantial investment. During the past year, Merck has been testing a DNA gag construct and an extensive range of CTL assays in preclinical studies. At this time, Merck plans to move its DNA vaccine, without an adjuvant, into a phase 1 trial in late 1999. The company is developing a virus vector vaccine for possible use in combination with its DNA product. The level of activity in the HIV vaccine program at Merck has reportedly increased, with researchers now taking an exhaustive and thorough development approach, exploring and optimizing gene sequences, CTL assays, adjuvant or delivery systems, and several possible vaccine combinations.

The company has been secretive about its efforts. Although Emini has met twice with David Baltimore’s AIDS Vaccine Research Committee, Merck has neither engaged in collaborations with NIH nor acknowledged partnerships with other companies. In 1998, Merck also lost three important DNA researchers to Chiron. It is unknown at this time whether Merck’s HIV DNA product will be immunogenic enough in its first human trials to justify further development and what Merck’s staying power is if the company sees disappointing immune responses during early clinical testing.

Pasteur Merieux Connaught

Pasteur Merieux Connaught (PMC), a subsidiary of Rhone-Poulenc, is one of the world’s leading vaccine manufacturers, producing vaccines for hepatitis B; influenza; herpes; whooping cough; diphtheria; measles, mumps, and rubella; bacille Calmette-Guérin; and tetanus. In 1998, PMC completed phase 3 trials on a new Lyme disease vaccine as well as a new pediatric combination vaccine for Haemophilis influenza B, diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough. PMC also conducted important research on new vaccines against meningitis, pneumococcus, and respiratory syncytial virus.

SmithKline BeechamLed by Michel Klein, the PMC HIV vaccine program is looking at five different vaccine approaches: canarypox vectors, DNA, lipopeptides, pseudovirions, and an oligomeric envelope subunit (o-gp160).