Text by Ted Williams

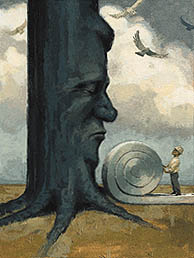

Illustrations by Tim Bower

George W. Bush called it a "Clinton-Gore land grab." But the President's move to protect America's roadless areas could be the boldest conservation act since Teddy Roosevelt. Now the fate of our last patches of uncut forest may depend on you.

On October 13, 1999, President Bill Clinton positioned himself on a scenic overlook in Virginia called Reddish Knob and, against the backdrop of the George Washington National Forest cooperatively aglow with autumn colors, announced what he accurately called "one of the largest land-preservation efforts in America's history." He was ordering the U.S. Forest Service to study and then propose how best to protect America's "roadless areas"--54 million acres of forest scraps, some as small as 1,000 acres, though the traditional minimum "roadless" designation is 5,000 acres. No other President had more boldly defied the will of Congress with an administrative land-protection order since 1907, when Theodore Roosevelt designated 21 new national forests covering 16 million acres in the eight days before Congress permanently stripped the chief executive of such power.

At this writing, the Forest Service is preparing a draft

environmental-impact statement (EIS) that it says should be out about the

time you receive this issue of Audubon. Public comments are vital because

they will help shape the final EIS, due out before November, and determine

the fate of about a quarter of our national forestland. Among the items

under debate are the minimum size of a "roadless area" and whether or not

our largest national forest--the Tongass, in Alaska--should be

exempt.

| Sidebar: What You Can Do

Stop a Road The fate of some of our best and wildest national forestland will depend on comments made in the next few weeks. Remember, you can make a difference, especially when you engage others. Three things you can do: 1) Act locally. To find out how many federal roadless acres are in your state, visit the Forest Service's web site: http://www.roadless.fs.fed.us/. The most important point to be debated is whether or not our largest national forest--the Tongass, in Alaska--should be exempted from protection as demanded by Senator Frank Murkowski and Representative Don Young. 2) Make yourself heard. Speak up at the public hearings that will be held during the spring and summer. Also, log on to the Heritage Forests Campaign web site, http://www.ourforests.org/, where you can send an e-mail postcard to the Forest Service, get campaign updates, and volunteer. Or write the Heritage Forests Campaign, c/o The National Audubon Society, 1901 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20006. 3) Tell others. Distribute this article. For reprint permission, write to Audubon Magazine--Reprints, 700 Broadway, New York, NY 10003, e-mail us at editor@audubon.org, or fax us at 212-477-9069. Please indicate the number of copies and means of distribution. |

Some of the response to President Clinton's announcement has been predictable. The American Forest & Paper Association, trade group of the forest-products industry, shrieked as if fondled by a vampire, spewing such gross misinformation as, "The next step will be zero cut on our public forests." And: "They are building a wall around the national forests.... The fire and diseases will spread to private forestlands and homes and towns." And: "This is an end run around Congress. It is up to Congress to designate wilderness areas." And: "Many people supplement their incomes by selling firewood salvaged from national forests. No more."

Property-rights zealots and politicians used the opportunity to get listened to. "There's no law that supports him.... What they are doing is illegal and unconstitutional," pronounced Perry Pendley, author of War on the West, to Salt Lake City's Deseret News. Senator Larry Craig (R-ID) accused "King William" of re-creating "feudal Europe," "lock[ing] up" the national forests "to all but an elite few," and making an "overt political move to shore up support for Prince Albert." Senators Frank Murkowski (R-AK) and Robert Smith (R-NH)--neither of whom had ever evinced the slightest interest in the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), except as it impeded their development plans--sent the Forest Service a seven-page missive about how the administration was violating NEPA by limiting public participation. Echoing the claim, the governors of Idaho and Montana--where roadless national forestland totals 15 million acres--sued.

In his 2,000-word announcement, Mr. Clinton invoked the name of Theodore Roosevelt 10 times. It was a strange sight. The president who had entered the White House emulating his own party's boy king of Camelot was leaving emulating the GOP's trust-busting, roughriding bull moose. What did it mean? Is an administrative ban on new roads on 54 million acres possible? Is it legal or even desirable? What will be the economic impacts? How will fish and wildlife be affected? How will recreation be affected? What does the public think of such a notion? What are Mr. Clinton's real motives? Who's really behind it?

The American Forest & Paper Association shrieked as if fondled by a vampire, spewing such gross misinformation as, "They are building a wall around the national forests."

Only the last of these questions elicits the same answer from virtually everyone you ask it of. The person behind the roadless initiative is a biologist, woodsman, and passionate fish and wildlife advocate named Michael Dombeck--a man who really does speak softly and who understands that, for this job at least, the stick he carries as chief of the Forest Service isn't big enough.

As a fishing guide in northern Wisconsin, as a fisheries scientist for the Forest Service, and as acting director of the Bureau of Land Management, Dombeck saw firsthand what roads do to public resources. Stabilizing, rehabilitating, and--where appropriate--doing away with roads became his top priority as he struggled to change the mission of his 30,000-person bureaucracy from resource extraction to resource stewardship. "Of all the things that we do on national forests, road building leaves the most lasting imprint on the landscape," he declared in January 1997, a month after he took office.

Everywhere he looked, Dombeck saw the costs of ill-conceived,

ill-designed logging roads measured in lost fish, wildlife, water, and

timber. During the winters of 1995-96 and 1996-97, for example, roads on

the Clearwater National Forest in Idaho caused about 700 landslides, which

sent heavily timbered mountainsides into rivers. In February 1996 almost

1,300 landslides caused by roads and clearcuts on the Siuslaw National

Forest in Oregon further stressed critically depressed salmon populations.

Even if the soil stays in place, many species, such as wolves, elk, and forest-interior birds, decline when woods are fragmented with roads; species such as grizzlies, lynx, and wolverines are apt to disappear. There are few large roadless areas on private land, so the 54 million acres that remain in our national forests--along with a few other federal holdings--are about all there is. It sounds like a lot when described as a quarter of all national forestland, but a more revealing description is 2.2 percent of America's 2.5 billion acres. The question Dombeck has been asking for four years is this: What's the rush to make these relict scraps like all the rest? The national forests are already laced with 380,000 miles of roads--enough to circle the globe 15 times--and the agency doesn't have the money to maintain 80 percent of them at the standards required by its own environmental and safety regulations. The current road reconstruction and maintenance backlog is $8.4 billion.

Before Dombeck prevailed on Congress to do away with the practice in 1998, the Forest Service financed elaborate roads under a system called "purchaser road credits." It would pay a timber company for building a road by giving it a discount on the timber it cut. If the road cost more than the timber was worth, the Forest Service would wind up owing the logging company trees. The system was a good part of the reason the public's trees didn't pay their way out of the public's woods. Dombeck was the first chief to admit these deficits; before he came on the scene, the agency had attempted to conceal them with trick arithmetic. Between 1992 and 1994, for example, the Forest Service claimed to have made $1.1 billion on timber sales--even as the Government Accounting Office revealed that it had lost $995 million. The more roads the Forest Service financed, the more money it could tell Congress it needed.

Dombeck's predecessor, Jack Ward Thomas--also a respected scientist and a reformer in his own right--had candidly informed the environmental community that he was going to log roadless areas because that was the only way he could get out the volume of timber he and Congress desired. Dombeck, on the other hand, hadn't been on the job a month when he told Congress this: "The unfortunate reality is that many people presently do not trust us to do the right thing. Until we rebuild that trust and strengthen those relationships, it is simply common sense that we avoid riparian, old-growth, and roadless areas." Because the Forest Service is funded in part by its own timber sales, road building and logging traditionally have taken precedence over all other forest uses. And Congress has pushed road building and logging because, under a bizarre arrangement established in 1908, local communities get 25 cents for every dollar the service earns in timber sales, virtually all of which is spent on schools or roads. So Dombeck's statement elicited howls from property-rights groups, western Republicans, and old-guard "timber beasts" in his agency.

Meanwhile, environmentalists remained skeptical. They had heard this kind of talk from the Clinton administration before. And in the midst of the talk, the President had signed the salvage logging rider, which basically said to the timber industry, "During the last half of 1996, environmental laws don't count. Under the guise of ėsalvaging' the public's timber after and even before it is killed by fire, insects, or microbes, you can hack it down without protecting public resources or bothering with public review. And while you're at it, help yourselves to old growth in spotted-owl reserves. Enjoy!" Was there any genuine courage and commitment behind the good-sounding talk of Clinton's young, untested Forest Service chief?

Dombeck detested purchaser road credits and other reverse incentives that worked against forest stewardship--such as the Knutson-Vandenberg Act of 1930, which lets the Forest Service retain timber-sale receipts in a trust fund for pet projects. He found powerful support from a coalition of environmentalists and conservative tax activists who called themselves the Green Scissors Coalition. Thanks in large measure to lobbying by that group, the House of Representatives came within a single vote of zeroing out the $42 million budgeted for road construction in national forests in 1997. In the Senate the vote was deadlocked. The political climate was right for action.

If Senator Craig has it right that the Clinton administration's real motive is to position Al Gore for the presidency, the plot has been two and a half years in the making. In January 1998 Dombeck announced a proposal to temporarily halt road construction in 130 of 156 national forests and to develop a fish-and-wildlife-friendly transportation policy. The moratorium became effective in February 1999, the same year Clinton's Office of Management and Budget shot down Dombeck's proposal to get rid of the Knutson-Vandenberg fund and all the other reverse-incentive trust funds, or "slush funds," as environmentalists call them. By removing the incentive to overcut, that single reform could have been--and may yet be, if Dombeck pulls it off--even more important to the long-term health of our national forests than protecting roadless areas.

One might have supposed that a proposal to reduce spending for roads that weren't needed, that couldn't be maintained, and that, in many cases, were illegal because they'd been authorized under ancient, discarded forest plans, would have elicited wild cheers from fiscal conser-vatives in Congress. But Senator Craig (chair of the Subcommittee on Forests and Public Land Management), Senator Murkowski (chair of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources), Representative Don Young (R-AK, chair of the Committee on Resources), and Representative Helen Chenoweth (R-ID, chair of the Subcommittee on Forests and Forest Health) informed Dombeck in writing that if he didn't back off, they'd reduce the role of the Forest Service to "custodial management." That is, they'd defund it, canceling all fish and wildlife enhancement, allowing landslides to obliterate roads, trails, and streams, and closing visitor information centers and campgrounds. If logging wasn't going to remain the dominant Forest Service program, they'd shut down all programs.

The chief's 1998 proposal elicited the following outburst from Young: "We need to just keep cutting the budget back until they [Forest Service brass] finally squeal." Chenoweth hauled Dombeck to three hearings in two weeks so that she could publicly roast him; when he came to Idaho to talk about the roads proposal, she had a federal marshal serve him a subpoena, dragging him out of his conference and back to Washington for yet another dog and pony show. Through it all, Dombeck revealed himself to be polite, good-humored, soft-spoken, and as tough as Teddy Roosevelt. While all the threatening rhetoric proved to be bluff, its viciousness taught him an important lesson: If he was going to save roadless areas, he wouldn't be able to do it alone. He'd need the bully pulpit of the presidency.

With support from the Heritage Forests Campaign--an educational drive directed by the National Audubon Society and funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts--the Forest Service's revolutionary roads policy evolved into an even more revolutionary roadless-areas policy. When President Clinton announced it last October, not all the response was predictable. Some was startling, especially the silence. Apart from the wind vented by the American Forest & Paper Association almost as a conditioned reflex when Mr. Clinton said "protection," the forest-products industry has been remarkably quiet. The real opposition to the initiative, reports Chris Wood, Dombeck's chief of staff, is coming from off-road-vehicle (ORV) groups. Loudest of these is a wise-use front for ORV manufacturers and extractive industries called the Blue Ribbon Coalition, which shouts that the administration is trying to shut down all public use of the national forests. It's hard to figure why the motorheads are making such a fuss, unless they're fund-raising. Restrictions on ORV use were never part of the President's proposal.

Politicians are hollering. Noting that roadless areas have traditionally been managed by the individual national forests with input from local residents, New Hampshire's Democratic governor, Jeanne Shaheen, attacked Mr. Clinton for setting "a terrible precedent" and "discouraging citizen involvement in the forest management planning process." Her vitriol set most of the presidential candidates into full cry when they took the stump during the New Hampshire primary. "The idea that Washington knows best and those local residents cannot be trusted to do what's right in their own backyard is the epitome of federal arrogance," puffed John McCain. George W. Bush--who had named as one of his natural-resource advisers libertarian guru Terry Anderson, who advocates privatizing public lands--expressed strong support for local control. On gaining the White House, Bush vowed, he'd overturn the "Clinton-Gore land grab." Even Bill Bradley accused the President of preempting "the local planning process," though he later backpedaled when scolded by environmentalists.

Where permitted, local control of national forests has brought economic and environmental ruin: landslides, sprawling clearcuts, silted rivers, endangered fish and wildlife, and single-species plantations subject to pest infestations and inhospitable to native fauna. Locals perennially demand that federally managed land be "given back," but in most cases it never belonged to them in the first place. And where it did belong to them, they abused it to the point that they violated the property rights of others. The White Mountains National Forest, for example, wouldn't even exist had it not been for the federal purchase of cut-out, farmed-out, washed-out land that no one else wanted. The devastation wrought by local control inspired Theodore Roosevelt to declare: "To skin and exhaust the land instead of using it so as to increase its usefulness, will result in undermining in the days of our children the very prosperity which we ought by right to hand down to them amplified and developed."

The national forests are already laced with 380,000 miles of roads, enough to circle the globe 15 times, and the agency doesn't have the money to maintain 80 percent of them.

What should be the role of Congress in all this? Is Mr. Clinton really guilty of "making an end run" around it? Well, sure. "But what's he supposed to do?" says Craig Gehrke, Idaho director of the Wilderness Society. "If you want to get things done, you bypass Congress. All it does now is stick riders on appropriations bills. Our delegation hasn't done anything on wilderness for 20 years." Daniel P. Beard, public policy director for the National Audubon Society, makes this point: "From 1964 to 1994 Congress steadily created new parks, refuges, wild-and-scenic rivers, scenic trails, and wilderness areas. When the Republicans took over six years ago, they made it very clear that they weren't interested in any of that. It all stopped. But there is compelling national support for these kinds of protections." Indeed there is. A national survey conducted last January by American Viewpoint, a Republican polling group, revealed that 76 percent of the public supports the President's proposal and only 19 percent oppose it. Five percent are undecided.

But are people like property-rights barker Perry Pendley correct when they deny the Forest Service's legal authority to administer protection (though not roads and clearcuts)? And is it only up to Congress to set aside wilderness, as the American Forest & Paper Association irately avers (not that Mr. Clinton has proposed any)? The answer to both questions is no, because--while the Forest Service can't designate "wilderness" under the Wilderness Act of 1964--it is fully empowered by multiple statutes to preserve wild land as de facto wilderness, imposing any restrictions it sees fit. In fact, before the Wilderness Act, Congress designated no national forest wilderness areas (or "primitive areas," as they were then called). It was done by the Forest Service. Nor is the agency violating NEPA. The law doesn't even require it to hold public meetings, but its environmental review has involved an unprecedented 190 public meetings around the nation--at least one in every national forest--and more are scheduled after the draft EIS is released. With the job not half over as of this writing, the Forest Service already has collected about half a million comments, the vast majority of them enthusiastic.

Critics of the proposal seem united in their notion that roadless areas require human tweaking to stay healthy. These critics see fire, insects, and microbes as threats to, not parts of, a natural forest. They fervently believe that unless humans get in there with heavy machinery and do things like salvage logging, the system will self-destruct. It's an interesting theory: Forests that sprang up in the wake of the retreating glaciers, 10,000 years before human settlement, are imperiled because they lack the roads they never had. But as Dombeck observes, roads are the greatest health risk forests face. Why, he asks, spend money building new ones when that same money could be spent on the 75 percent of national forestland that already has roads and where genuine, road-caused problems such as erosion, declining water quality, and exotic-plant proliferation are rampant? Moreover, no reliable scientific evidence shows that logging is a method of fire prevention. In fact, most human-caused forest fires start on clearcuts because they allow sun and wind to desiccate fuels and because heavy equipment produces heat and sparks.

Why has the forest-products industry been so silent since its October tantrum? The President may have provided the answer himself when he noted that only 5 percent of our country's timber comes from national forests, and less than 5 percent of that 5 percent comes from roadless areas. Roadless areas don't have roads because they tend to be steep and inaccessible or because they are mostly rock and ice. If it had been cost-effective to log roadless areas, we wouldn't have any.

National forest timber has never been a major or (for the public at least) even a profitable resource. But 80 percent of the nation's rivers originate in national forests, and 60 million Americans depend on national forest water. "This is where aquifer recharge occurs," says Dombeck, who likes to call his agency "the largest water company in the U.S." He figures that if the Forest Service were allowed to sell its water as it sells its timber, it would have an embarrassment of riches--a minimum of $3.7 billion a year. National forests also provide the public with its single largest source of outdoor recreation. According to the Forest Service, outdoor recreation contributes 31.4 times more income to the nation's economy than logging and creates 38.1 times more jobs.

But the dollar value of roadless national forestland goes far beyond water and recreation, explains economics professor Ed Whitelaw, of the University of Oregon, who uses the term second paycheck to describe how local economies are stimulated by pleasant, healthful surroundings. "Workers in Chicago and Los Angeles typically earn wages 5 to 15 percent higher than they can earn in Oregon," he observes. "So why hasn't everybody moved there? Back in the 1980s the conventional wisdom was, economics equals jobs and income. Not only was the economic importance of environmentally destructive industries vastly overstated, but the economic importance of environmental quality wasn't appreciated. When most folks think of regional growth, they think, Okay, you get the jobs first and then the people follow. Fur in Hudson Bay 200 years ago. Staples--things you dig up, cut down, kill, and then export. Each of those activities generates jobs, and the workers bring families. Well, it turns out that every regional economy around the world has another mechanism: people first, jobs follow. Those areas that have the comparative advantages that attract the people first will grow."

During the spotted-owl wars--when Whitelaw's radical ideas required him to retain the services of a bodyguard--some of the same politicians now attacking the President's roadless initiative were predicting a collapse of the Northwest's economy and the loss of 100,000 jobs. Instead, the economy boomed. In an April 1999 report entitled "The Sky Did NOT Fall: The Pacific Northwest's Response to Logging Reductions," Whitelaw and his associates at ECONorthwest, his private consulting firm, made this observation: "The Pacific Northwest weathered virtually unscathed the national economic recession that occurred at about the same time as Judge Dwyer's [spotted-owl] ruling, and both Oregon and Washington have consistently outperformed the national economy throughout the 1990s. While timber harvests fell 86 percent on federal lands and 47 percent overall from their peak in 1988 to 1996, employment in the lumber-and-wood-products industry, which constitutes the bulk of the timber industry in the Pacific Northwest, fell 22 percent. In contrast, total employment rose 27 percent."

If roadless areas are really to be protected, a few things need to happen fast: First, the President must stand up to western Republicans, something that hasn't always been easy for him. Senator Craig has strongly hinted that he'll attach a rider on an appropriations bill to defund the EIS process. When this happens, Mr. Clinton will have to be ready with a veto.

Second, the public will have to turn up the volume as it voices its support. This applies especially to the nation's sportsmen. A poll commissioned by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Alliance and conducted by Responsive Management of Harrisonburg, Virginia, shows that 83 percent of hunters and 86 percent of anglers favor keeping roads out of roadless areas. But hunters and anglers are not talking, and the same poll reveals their vulnerability to the seductions of wise-use groups: 41 percent of the hunters and 45 percent of the anglers couldn't even name the agency responsible for managing our national forests. "There are 50 million hunters and fishers," comments Tim Richardson, the alliance's deputy director. "They are potentially the biggest force on land-use and natural-resource issues in the country. In sheer numbers they dwarf the environmentalists. But there's an education job that's huge and an apathy tradition in recent years to overcome."

One of the problems is that sportsmen aren't getting adequate leadership from private and state game managers. No example is more outrageous than the attack on the President by the Ruffed Grouse Society, which imagines that its members will have more birds to shoot if clear-cutting is extended to roadless areas. Similar noise issues from some of the state fish and wildlife agencies, especially in the Southeast. Of all the interest groups, game managers should be most supportive of road control. But many are fighting roadless-area protection in national forests because they see it as a plot for more wilderness, a designation that would limit their employment opportunities in stocking native and alien game fish and in growing native and alien plants for deer and turkey. Moreover, their hired spokesperson--Max Peterson, the executive vice-president of the International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies and a former chief of the Forest Service--has labored to defeat Dombeck's crusade. The moratorium on roads was wrong, he told the House Committee on Resources, and the decision to build a road or not "cannot logically be made from the top down or by those of us within the Beltway without detailed knowledge of the area."

Perhaps Mr. Clinton's motive in trying to protect a quarter of our national forestland really is to position Al Gore for the presidency, and the whole proposal was Mike Dombeck's idea anyway. If the administration manages to pull it off, should America remember Mr. Clinton as an environmental hero? Yes, because history judges presidents not by motives but by accomplishments and less by initiatives they conceive than by those conceived and implemented by the people with whom they build their administrations. Much of Theodore Roosevelt's mystique, for example, issues from the policies of his enlightened Forest Service chief, Gifford Pinchot.

But how will Mr. Clinton be judged if he doesn't catch T.R.'s ghost--if the EIS process moves too slowly, the Democrats lose the White House, and Dombeck has to go looking for a job? Maybe the President and the nation would do well to recall these words, uttered by Theodore Roosevelt in 1899, two years before he became commander-in-chief: "Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in the gray twilight that knows not victory nor defeat."

Ted Williams grew up fishing, hiking, and camping in

the White Mountains National Forest of New Hampshire..

© 2000 NASI

Sound off! Send a letter to the

editor

about this piece.