Budget Scramble

Social Security, Medicare Surpluses Are Key Prize

as Federal Ledger Returns to Red

By Walt Duka

April 2002

A year ago political leaders of all persuasions, including President

Bush, vowed that the Social Security surplus would be used only to pay

benefits or to reduce the national debt.

Today the so-called lockbox that was supposed to protect this surplus

lies shattered. As red ink has once again begun to flow over the federal

budget, part of the trust fund reserves has already been borrowed for

other purposes. And budget officials expect borrowing to continue for at

least eight more years.

| Borrowing from the trust funds "does

not affect Social Security's ability to pay

benefits." |

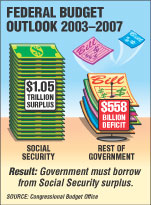

The turnaround has set off a budget scramble in which the Social

Security and Medicare surpluses—now at $1.3 trillion and the only

surpluses left—are the key prize. And how this money is used, and what the

impact will be, have become major concerns for many Americans.

The Social Security surplus results from the trust fund taking in more

in payroll taxes than it pays out in benefits—a deliberate buildup to help

prepare for the coming upsurge of baby-boomer retirements.

"The first thing people should be clear about is that this borrowing

does not affect Social Security's ability to pay benefits," says John

Rother, AARP director of policy. "The trust fund is intact and still

collecting interest on its Treasury bonds."

The main effect of continued borrowing, he says, will be on the

economy. If the trust fund surplus is not used to reduce the national

debt, as it was for four recent years, that debt will not be paid off and

interest payments will be higher.

Rother says it is AARP's position that as trust funds continue to be

tapped, this money should be used as it was intended. "The Social Security

and Medicare trust funds were created to ensure the health and retirement

security of our aging population," he says, "and their surpluses should be

used for Social Security and Medicare before anything else."

Others think differently. Bush, in his 2003 budget, proposes big

increases in defense and national security spending—increases that, for

the most part, Congress is likely to approve. But while he earmarks $190

billion over the next decade for a prescription drug program, the

president would also make last year's tax cuts permanent and add new tax

cuts—a move many oppose.

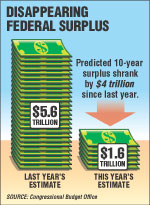

The nonpartisan

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) says the current budget squeeze grows

out of the economic recession and recent laws, especially last year's

$1.35 trillion package of tax cuts and emergency spending related to Sept.

11. These factors combined to lop off an astounding $4 trillion from the

decade of surpluses forecast just a year ago.

Almost all that loss stems from the drying up of expected

surpluses from the non-Social Security side of the federal ledger. In

contrast, the CBO says Social Security will continue to pile up hefty

surpluses over the next decade.

Borrowing from the trust fund resumed last year, when $33 billion was

diverted to other uses. This year $152 billion more is expected to be

borrowed, and the CBO sees the trend continuing each year through

2009.

Economists almost all agree that short-term deficit

spending is acceptable, even desirable, during a recession. They say it

can help put the economy in gear and pump up government revenues. But they

warn that large, long-term deficits could force harsh cutbacks and tax

increases down the road.

The multitrillion-dollar question therefore is, How long will deficits

last?

Bush says that if Congress follows his plan, balance could be restored

to the overall (or "unified") budget in 2005. His approach involves making

significant cuts in certain programs and borrowing from the Social

Security surplus.

But others, like Sen. Kent Conrad, D-N.D., chairman of the Senate

Budget Committee, believe the president paints too rosy a picture. "We now

face a decade of red ink," Conrad said at a recent hearing. And "the

biggest reason," he continued, "is because of the tax cut."

Economists say two factors will largely determine whether or not

deficits become a serious problem: how fast the nation recovers from

recession and whether government spending is kept at reasonable

levels.

Like most economists, Robert D. Reischauer, president of the Urban

Institute, a Washington think tank, believes the recession may be behind

us but that recovery may be slow. He's concerned, however, that "it's

going to be real difficult to impose fiscal discipline" on Congress.

"The easy [budget] areas on which to impose discipline have been

used up," he says, and divided government and the narrow balance of

political power "create pressures to spend more and cut taxes more." "The easy [budget] areas on which to impose discipline have been

used up," he says, and divided government and the narrow balance of

political power "create pressures to spend more and cut taxes more."

Larry Sabato, a political scientist at the University of Virginia,

shares that concern. "Once you go into deficit," he says, "the restraints

are gone for all practical purposes." He believes this will especially be

the case as the parties jockey for public favor before the November

elections.

Analysts foresee

a series of running battles in coming months as Congress debates how much

to spend on domestic programs. They also expect a rough-and-tumble war of

words to take place over tax cuts, since some Democrats favor freezing

cuts that have already been approved but not yet implemented—a position

directly opposed to the president's.

Daniel Mitchell, a senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a

conservative Washington think tank, backs most of the president's

proposal. He says speeding up the tax cuts is necessary to boost the

economy.

"A tax cut delayed," he says, "is an economic benefit deferred."

Richard Kogan, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, takes an opposite tack. "Seventy-one percent of the tax cut,"

he says, "went for people in the top one-fifth of the income spectrum." As

a result, he favors "not locking into place portions of the tax cut that

haven't yet occurred."

Although the tax debates are expected to raise political tempers on

Capitol Hill, most experts believe that neither a speeding up nor slowing

down of the tax cuts will take place.

Reischauer says the nation is coming off several years of surplus and

is therefore much better off than it was when deficits soared in the 1980s

and early 1990s.

"Compared to our expectations [of huge surpluses] of a year or two ago

the situation has deteriorated significantly," he says. "But we shouldn't

pretend it's worse than in fact it is."

Congress can still control the situation. "If we slip back into serious

budget difficulties," Reischauer says, "it will be because of decisions

yet to be made."

Still, the University of Virginia's Sabato adds a note of caution.

"People should be concerned about the budget situation," he says, "because

if you look back on the history of budget deficits, they tend to build on

one another."

|