|

| To gain a better understanding of the funding

challenge facing the clean water and drinking water

industries, the Environmental Protection Agency conducted a

study to identify whether there is a quantifiable "gap"

between current levels of spending and projected water

investment needs over the 20 year period from 2000 to 2019.

|

| The General Accounting Office also released a

recent report on Water Infrastructure: Information on

Financing, Capital Planning, and Privatization. Both reports

were requested by Congress to help with planning federal

funding for water. |

| EPA's Clean Water and Drinking Water

Infrastructure Gap Analysis found that a significant funding

gap could develop if the nation's utilities maintain current

spending and operations practices. |

|

The Gap Analysis presents the projected funding gap over

the 20–year period in two ways: a "no revenue growth" scenario

that compares the projected need to current spending levels;

and a "revenue growth" scenario that assumes spending will

increase by 3 percent per year. This annual increase

represents a real rate of growth of 3 percent over and above

the rate of inflation — a projection which is consistent with

long-term growth estimates of the economy, according to EPA.

|

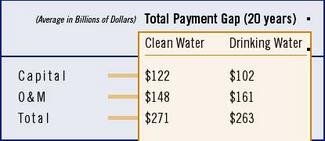

| Under the "no revenue growth" scenario, the

analysis estimates a total capital payments gap of $122

billion, or about $6 billion per year, for clean water and

$102 billion, or about $5 billion per year, for drinking

water. The O&M gap is estimated at $148 billion, or $7

billion per year, for clean water and $161 billion, or $8

billion per year, for drinking water. |

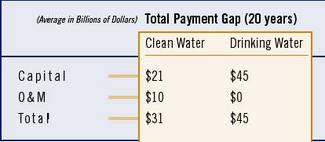

| Under the "revenue growth" scenario, the capital

gap is $21 billion, or about $1 billion per year for clean

water and $45 billion, or about $2 billion per year, for

drinking water. The O&M gap is estimated at $10 billion,

or $0.5 billion per year, for clean water, while no O&M

funding gap would occur for drinking water. |

| Each of these numbers represents an average

within a range of estimates. Under the assumptions used to

calculate the funding gaps, some of the models predict that

total spending will exceed the total need over the next 20

years. |

| In broad terms, the gap analysis concludes that

clean water and drinking water systems will need to use some

combination of increased spending and innovative management

practices to meet projected needs. |

| EPA acknowledged that its study understates

future spending and ignores other measures, such as asset

management processes or capacity development, that systems

could adopt to reduce both capital and O&M costs. |

| In reality, increasing needs will likely prompt

increased spending, EPA said. However, the analysis presents

an approximate indication of the funding gap that will result

if the nation's utilities ignore the challenge posed by an

aging infrastructure network. |

| |

| In developing its Gap Analysis, EPA noted that

further research would help better quantify the infrastructure

gap. For example: |

• A better inventory of the nation's clean water

and drinking water capital stock and its condition is needed.

That includes developing an improved picture of the remaining

life of capital assets such as treatment plants, piping

networks and storage systems. Such information would greatly

improve decision-making about investment needs for

maintaining, upgrading, and expanding infrastructure.

• The

relationship between O&M needs and capital stock is not

fully understood. A more refined approach than the one adopted

in the Gap Report would investigate how O&M needs vary as

a function of gross (not net) capital stock and the age or

condition of the capital stock. These data, other than in

purely speculative form, are not yet available.

• Clean

water and drinking water systems will incur significant costs

over the next 20 years as they expand capacity to serve

current and future growth. Methods for estimating capital

investment needs associated with growth and changes in service

standards were excluded from the analysis. |

|

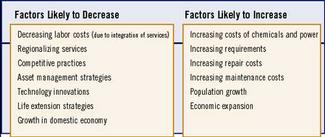

| A Qulitative Assesment of the

Sensitivity of the Gap Estimate |

According to EPA, its analysis would benefit from research

into an array of issues that ultimately will determine, or at

least influence, the scale of future capital investment needs.

These issues will also determine how future capital investment

needs are met. More research is needed on a variety of topics.

For example: |

• How implementation of best management

practices, including asset management and capacity

development, would benefit the funding gap.

•

Restructuring, integrating, and combining water and wastewater

utilities to generate better economies of scale.

• Pricing

policies and their effect on demand for water

•

Demographic shifts within the United States

Efficiencies

gained or lost due to the installation of the latest

technology

• Trends in operating costs — for example, the

cost of chemicals and energy

• Criticality analysis —

which components of a system should take precedence for

investment due to age, condition, and importance) |

| Copies of the Gap Analysis and the Needs Surveys

are available from the Safe Drinking Water Hotline at

800-426-4791, the Office of Water Resource Center at

800-832-7828, and on the Internet at www.epa.gov/ow. |

| |

| Congress asked GAO to examine several issues

relating to the funding available to help meet the capital

investment needs of the nation's drinking water and wastewater

facilities. Given the broad scope of the request, GAO agreed

to provide the information in two reports. The first Water

Utility Financing and Planning report, issued in November

2001, addressed the amounts and sources of federal and state

financial assistance for drinking water and wastewater

infrastructure during fiscal years 1991 through 2000. |

| This second report, issued in September,

examines how the amount of money generated through user

charges and other local funding sources compare with the cost

of providing service at public and private drinking water and

wastewater utilities serving populations greater than 10,000.

It also discusses how such utilities manage existing capital

assets and plan for needed capital improvements, and what

factors influence private companies' interest in assuming the

operation or ownership of publicly owned drinking water and

wastewater facilities. |

|

| No Revenue Growth Scenario: 2000 -

2019 |

GAO found the amount of funds obtained from user charges

and other local sources of revenue was less than the full cost

of providing service — including operation and maintenance,

debt service, depreciation, and taxes — for over a quarter of

drinking water utilities and more than 4 out of 10 wastewater

utilities in their most recent fiscal year. |

|

| Revenue Growth Scenario: 2000 -

2019 |

While revenues from user charges and other local sources

were adequate to cover at least operation and maintenance

costs for nearly all of the utilities; an estimated 29 percent

of the utilities deferred maintenance because of insufficient

funding. Revenues from user charges accounted for most of

utilities' locally generated funds — at least three quarters

of all funds from local sources for at least three-quarters of

utilities. |

| GAO's survey found that more than a quarter of

utilities lacked plans recommended by utility associations for

managing their existing capital assets, but nearly all had

plans that identify future capital improvement needs. Among

the utilities that had plans for managing their existing

assets, more than half did not cover all their assets or

omitted key plan elements, such as an assessment of the

assets' physical condition. |

| In addition, while most utilities had a

preventive rehabilitation and replacement program for their

pipelines, for about 60 percent of the drinking water

utilities and 65 percent of the wastewater utilities, the

actual rate of rehabilitation and replacement in recent years

was less than their desired levels, and many had deferred

maintenance, capital expenditures, or both. |

| Many utilities also had plans for financing

their future capital needs, but nearly half believed that

their projected funding over the next 5 to 10 years would not

be sufficient to meet their needs. |

| GAO found that revenues from user charges

exceeded the cost of service at an estimated 39 percent of the

drinking water utilities and 33 percent of the wastewater

utilities. (For the purpose of this analysis, GAO defined a

utility's cost of service as operation and maintenance

expenses, taxes, depreciation, and debt service.) |

| When revenues from user charges were combined

with funding from other local sources, such as hook-up and

connection fees and sales of services to other utilities, an

estimated 71 percent of the drinking water utilities and 59

percent of the wastewater utilities covered their cost of

providing service. |

| According to GAO's survey results, about 85

percent of drinking water utilities and 82 percent of

wastewater utilities covered at least the operation and

maintenance portion of the cost of providing service using

revenues from user charges alone. Moreover, adding other

locally generated funds to the user charges, about 93 percent

of the utilities covered their operation and maintenance

costs. |

| GAO found that more than half of utilities whose

revenues from user charges and other local sources did not

cover their cost of providing service raised their rates two

times or less during the 10-year period from 1992 to 2001.

Overall, GAO found no statistically significant differences in

the frequency of rate increases between the utilities that did

not cover their costs and those that did. |

| A significant percentage of drinking water and

wastewater utilities—about 27 percent and 31 percent,

respectively—did not have plans for managing their existing

capital assets, although some utilities were in the process of

developing such plans. |

| Further, of the utilities with plans, more than

half did not include all of their assets or omitted one or

more key elements recommended by industry associations; for

example, 16 percent of drinking water utilities' plans and 21

percent of wastewater utilities' plans did not include

information on the condition level at which the utility

intends to maintain the assets. GAO found no statistical

differences among utilities of different sizes with regard to

the inclusion or exclusion of any of the key elements in their

asset management plans. However, GAO found that the plans

developed by privately owned drinking water utilities tended

to be more comprehensive than those developed by publicly

owned utilities. |

| According to GAO's survey results, some

utilities had significant portions of pipelines in poor

condition; for example, more than one-third of the utilities

had 20 percent or more of their pipelines nearing the end of

their useful life. Nevertheless, for about 60 percent of

drinking water utilities and 65 percent of wastewater

utilities, the actual levels of pipeline rehabilitation and

replacement in recent years were less than the utilities'

desired levels. |

| For example, GAO's survey indicates that roughly

half of the utilities actually rehabilitated or replaced 1

percent or less of their pipelines annually, even though an

estimated 89 percent of drinking water utilities and 76

percent of wastewater utilities believed that a higher level

of rehabilitation and replacement should be occurring. |

| Further, in each of three

categories—maintenance, minor capital improvements, and major

capital improvements—about one-third or so of the utilities

had deferred expenditures in their most recent fiscal years,

and 20 percent had deferred expenditures in all three

categories. With one exception, there were no statistically

significant differences among utilities of different sizes;

however, GAO found that public drinking water utilities were

more likely than their privately owned counterparts to defer

maintenance and major capital projects. |

| Copies of the General Accounting Office report

on Water Infrastructure: Information on Financing, Capital

Planning, and Privatization, can be downloaded in PDF format

at http://www.gao.gov/. |

| WaterWorld November,

2002 |