TEA-21: What it Means for

America and Our Wildlife

INTRODUCTION

The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st

Century was enacted June 9, 1998, authorizing

$217 billion for the Federal surface

transportation programs for highways, highway safety,

and transit for the 6-year period 1998-2003.

As successor to the Intermodal Surface

Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA), TEA-21

continued the transformation of our 1950s-era highway

building program into a flexible transportation program.

Both have heralded a revolution in how America executes

transportation policy -- shifting primary responsibility

from the federal government to state and local levels.

More emphasis is placed on building communities than on

building roads. Priorities changed to improved planning,

environmental protection and spending flexibility for

greater transportation choice.

Hallmarks of this new policy include:

-

Flexible funding for highways, transit

and other uses

-

Decisions on spending are made through

inclusive planning at state and local

levels

-

Significant funding is reserved for

maintenance of existing infrastructure

-

Set-aside funds are available for

alternative transportation and measures for

reducing the negative impacts on our

environment

-

Emphasis on public safety

-

Research and technology

TRANSPORTATION AND THE ENVIRONMENT

| For the last century, automobiles and the

roads they require have been the dominant force

shaping the modern American landscape. We have

more cars per capita than any other nation in the

world. Our interstate highway system is unrivaled;

connecting major metropolitan areas and providing

the basis for our transportation

infrastructure. |

|

However, our

mobility comes with a price. Nearly 4 million miles

of roadways and 200 million vehicles keep Americans

moving, but has had a devastating impact on our

environment. Transportation is the leading source of

overall air pollution; a primary consumer of wetlands;

farmland and open space; and a leading contributor to

solid waste, water pollution and natural resource

consumption.

ISTEA and

TEA-21 have attempted to address these problems, with

the following programs:

§ 1110 CMAQ

($8.1 billion)

The Congestion

Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement program provides

a flexible funding source to State and local governments

for transportation projects and programs to help meet

the requirements of the Clean Air Act. Eligible

activities include transit improvements, travel demand

management strategies, traffic flow improvements, and

public fleet conversions to cleaner fuels, among others.

Funding is available for areas that do not meet the

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (nonattainment

areas), as well as former nonattainment areas that are

now in compliance (maintenance areas). Funds are

distributed to States based on a formula that considers

an area’s population by county and the severity of its

air quality problems within the nonattainment or

maintenance area.

Title VI Ozone

and Particulate Matter Standards (PM)

In 1997,

Congress released new and revised National Ambient Air

Quality Standards (NAAQS) for ozone and particulate

matter (PM). Included in the PM NAAQS were new standards

for PM2.5—fine particles less than 2.5 microns. TEA-21

ensures the establishment of the new monitoring network

for PM2.5 and, within appropriated totals under the

Clean Air Act, requires the Administrator of the

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to provide

financial support to the States for 100 percent of the

cost of establishing and operating the

network.

§ 1202 Bicycle

Transportation and Pedestrian Walkways

TEA-21

continues and expands provisions to improve facilities

and safety for bicycles and pedestrians. National

Highways System funds are now available for pedestrian

walkways and consideration of bicyclists and pedestrians

is required in the planning process and facility

design.

§ 1221

Transportation and Community and System Preservation

Pilot Program ($120M)

States, local

governments, and metropolitan planning organizations are

eligible for discretionary grants to improve the

efficiency of transportation systems; reduce

environmental impacts of transportation; reduce the need

for costly future public infrastructure investments;

ensure efficient access to jobs, services, and centers

of trade; and examine private sector development

patterns and investments that support these

goals.

From http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/tea21/sumenvir.htm

TRANSPORTATION

AND WILDLIFE

These programs

address threats to the environment, but are aimed

essentially at the human environment, and do very

little to protect the natural environment, and

wildlife habitat. CMAQ and PM standards are designed to

reduce smog and air pollution in urban areas. Bike and

pedestrian facilities are designed to reduce congestion

on highways. To be sure, smog and pollution have a

negative impact on wildlife habitat. However, roads and

highways impact wildlife on many levels, beyond air and

water pollution.

1. Mortality

from road construction

The actual

construction of a road, from clearing to paving, will

often result in the death of any sessile or slow-moving

organisms in the path of the road. Obviously, trees and

any other vegetation will be removed, as well as any

organisms living in that vegetation.

2. Mortality

from collisions with vehicles

Roadkill is the

greatest directly human-caused source of wildlife

mortality throughout the U.S. More than a million

vertebrates are killed on our roadways every

day.

3.

Modification of animal behavior

The presence of

a road may cause wildlife to shift home ranges, and

alter their movement pattern, reproductive behavior,

escape response and physiological state. When roads act

as barriers to movement, they also bar gene flow where

individuals are reluctant to cross for

breeding.

4.

Alteration of the physical environment

A road

transforms the physical conditions on and adjacent to

it, creating edge effects with consequences that extend

beyond the white lines. Roads alter the following

physical characteristics of the environment: soil

density, temperature, soil water content, light, dust,

surface water flow, pattern of run-off, and

sedimentation.

5.

Alteration of the chemical environment

Maintenance and

use of roads contribute at least five different general

classes of chemicals to the environment:

a. Heavy metals

- gasoline additives

b. Salt - de-icing

c. Organic

molecules - dioxins, hydrocarbons

d. Ozone - produced

by vehicles

e. Nutrients – nitrogen

6. Spread of

exotics

Roads provide

opportunities for invasive species by:

a. providing

habitat by altering conditions;

b. stressing or

removing native species; and

c. allowing easier

movement by wild or human vectors.

7. Increased

use of areas by humans

Perhaps the

most pervasive, yet insidious impact of roads is

providing access to natural areas and encouraging

further development. As our cities and towns sprawl

across the landscape, more and more wildlife habitat is

forever lost to strip malls and parking

lots.

TEA-21 AND

WILDLIFE

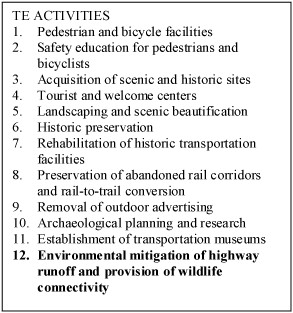

Thanks to the

efforts of Defenders, TEA-21 did contain one program

that had direct benefits for America’s wildlife. The

Transportation Enhancements (TE) program had been

instituted during ISTEA , which set aside 10% of Surface

Transportation Program (STP) funds for small-scale

projects that are initiated at the local level and

enhance the transportation experience, but are generally

not included in the normal routine of planning and

building highways. Common examples of TE activities are

construction of bike and walk trails and the

preservation of our scenic and historic resources as

they exist in a transportation context.

TEA-21 included

an expanded list of eligible TE activities, including

funding for provision of wildlife habitat

connectivity. Recognizing the inherent conflict

between wildlife and transportation, this category

covers projects such as wildlife crossings, underpasses

and overpasses.

TEA-21 is up

for reauthorization in 2003, and Defenders will be hard

at work to continue improving America’s transportation

in policy and practice.

INFORMATION

TEA-21

User’s Guide

The Guide is an in-depth look at

the policies and funding contained in TEA-21. It

explains TEA-21's major features, points out key

opportunities for making progress on the ground, and

explores some potential pitfalls.

Transportation

Equity Act for the 21st Century (P.L.

105-178): An Overview of

Environmental Protection

Provisions

by Congressional Research

Service.

Intermodal

Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 -

Summary

Message by (then) Transportation

Secretary Skinner.

Federal

Highway Administration (FHWA) TEA-21 Web

site

Contains the full text, cross reference,

summaries, fact sheets, funding tables, information

exchange and publications.

|