| |||

CAFE MENUTherese Langer CAFE 40 Miles per Gallon An often-proposed fuel economy target for the next 10 years. Close the Light Truck Loophole Introduced by Senators Feinstein, Snowe et al. in S.804. Sets light truck fuel economy standards at 27.5 mpg in 2007, bringing trucks up to the car standard. Raises the upper weight limit on vehicles subject to fuel economy standards from 8,500 lbs. to 10,000 lbs. HR.4 The fuel economy provision in the House Energy Bill. Requires a 5 billion gallon reduction in gasoline consumption in the period 20042010. Extends the dual-fueled vehicle credit for 4 years. Drill the Arctic Another approach to reducing U.S. dependence on oil imports. Introduction In this paper we describe a menu of approaches to updating the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards for cars and light trucks. The papers purpose is to provide a basis for comparison of options by using a uniform approach to analyzing the corresponding oil savings. The three proposals discussed are: (1) a 40 mile-per-gallon combined car-truck standard; (2) closing the "light truck loophole," as set out in S. 804; and (3) the fuel efficiency provisions of the House Energy Bill passed last summer. Also included is a profile of drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as another approach to reducing U.S. dependence on imported oil. The calculations here show oil savings relative to a "business-as-usual" scenario. The calculations require assumptions about future trends and other factors about which there is some uncertainty. Our assumptions include the following:

We made these choices, within the range of reasonable assumptions, to give a conservative estimate of the oil savings attributable to an increase in fuel economy standards. 1. 40 Miles per Gallon A combined car/truck fuel economy in the vicinity of 40 mpg has been proposed on various occasions over the past decade as an achievable near-term fuel economy target. Recent studies have confirmed the feasibility of this target by exploring in detail the strategies that could be applied to reach it. A study published by ACEEE, for example, describes packages of technological improvements that will or could become widespread over the next 1015 years and the fuel economy increases each would imply.3 The study was based on an engineering simulation of combinations of technologies applied to five existing vehicles representing the major passenger vehicle types. Their technology package yielding a fleet-wide average of 41 mpg included the following elements:

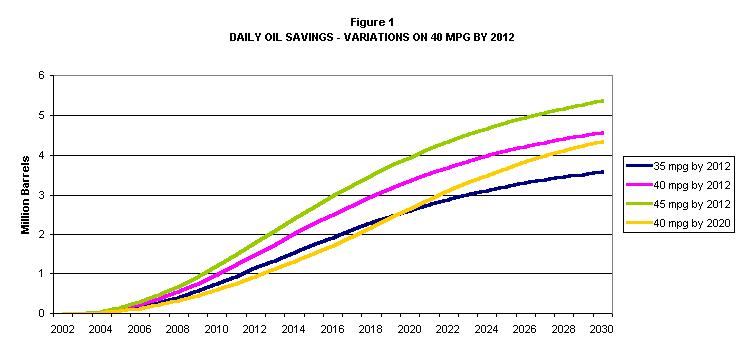

This package does not rely on hybrid vehicle technology. Its per-vehicle cost would be less than the expected increase in vehicle price (in constant dollars) over the same period, absent any fuel economy improvements. A recent report of the National Research Council's (NRC) Committee on the Effectiveness and Impact of Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards4 concludes that a fleet-wide fuel economy in the low to mid-thirties is achievable. The difference between ACEEE and NRC estimates is explained in large part by the fact that the latter excludes weight reduction as a technique for raising fuel economy to avoid any concerns about the safety implications of the strategies it investigated. The ACEEE report, by contrast, uses targeted weight reduction to not only complement fuel efficiency technologies, but also enhance highway safety. This is accomplished by reducing significantly the weights of heavy vehicles, which narrows the weight discrepancy between larger and smaller vehicles. Relative vehicle weight is a factor in the severity of many two-vehicle crashes, and this strategy mitigates that problem. A standard of 40 mpg by 2012 would reduce oil consumption by about 1.5 million barrels per day by 2012 and 3.4 million barrels per day by 2020. Figure 1 shows the sensitivity of oil savings to changes in the miles-per-gallon target and the date of achieving that target. Daily oil savings associated with targets of 35, 40, and 45 mpg, and for target dates of 2012 and 2020, are shown. In all cases, the improvements are phased in at a constant rate from 2003 to the relevant target date.

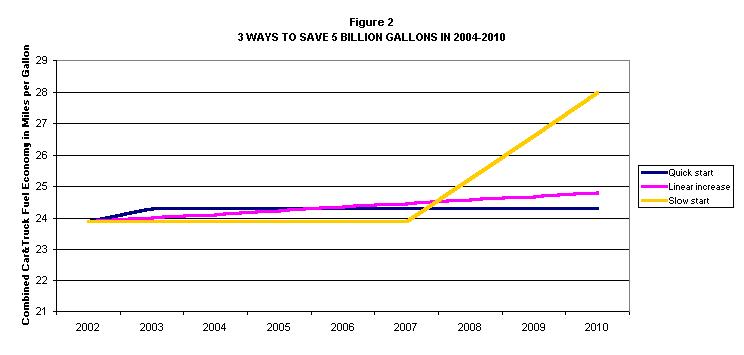

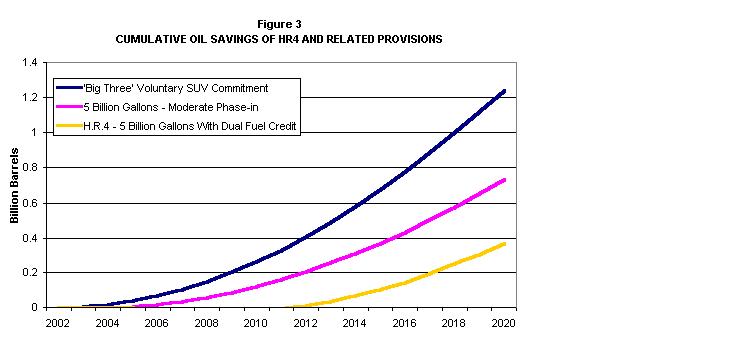

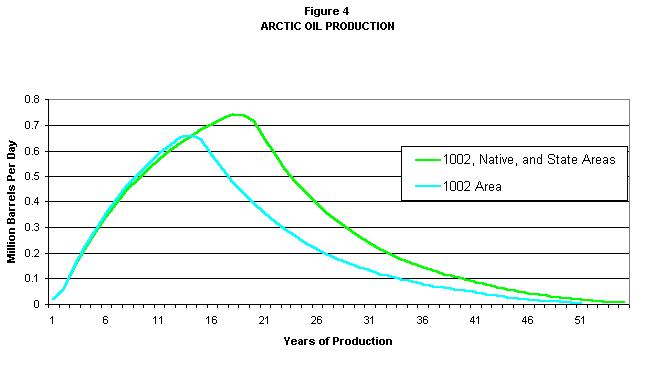

2. Close the Light Truck Loophole The current light truck CAFE standard is 20.7 mpg, while the car standard is 27.5 mpg. The light truck market has grown from 19% in 1975 to 47% in 2001, and the vast majority of these vehicles are now used as car substitutes.5 A given percentage improvement in fuel economy of light trucks will save more oil than the same percentage improvement in cars, and there is widespread acknowledgement that light trucks generally have a higher potential for fuel economy improvement than cars do. The NRC CAFE committee report, for example, states: "For mini-vans, SUVs, and other light trucks, the potential for reductions in fuel requirements is quite significant compared with smaller passenger cars."6 The ACEEE study cited above achieved a 41 mpg fleet through technologies that would double sport utility vehicle fuel economy while raising the fuel economy of small cars by only 57%.7 For all of these reasons, it is often proposed that efforts to raise fuel economy should start with light trucks. Senators Feinstein and Snowe introduced S.804 in May 2001 to close the "light truck loophole." The bill would raise the truck standard to 27.5 mpg in 2007, bringing trucks up to the car standard. It also would set milestones of 22.5 mpg in model year 2003 and 25 mpg in 2005. These standards would save a half-million barrels of oil daily by 2010. Savings would exceed a million barrels a day in 2017. While it is sometimes suggested that a lower standard for trucks is appropriate given their larger size, the fact is that 27.5 mpg is an achievable standard for trucks that would help to alleviate some of the problems that have been aggravated by the existence of separate car and truck standards. One such problem is the disproportionate increase in fatalities from car/truck collisions.8 Closing the light truck loophole may induce manufacturers to reduce the weights of some of their heaviest vehicles. While weight reduction in lighter vehicles has raised safety concerns in the past, the light-weighting of the heavier end of the fleet would improve safety. Once the loophole has been closed, car and truck standards could be combined and raised to a more ambitious level. S.804 also lifts the upper weight limit on vehicles that are subject to CAFE standards from 8,500 to 10,000 lbs. (gross vehicle weight). This is intended to prevent manufacturers from increasing the weight of their heaviest passenger vehicles, as some have done, to avoid fuel economy requirements. It is difficult to calculate the oil savings that this provision would bring because fuel economies are not reported currently for these heavier ("Class 2b") light trucks. But to judge from a sampling of vehicle sales data, the number of Class 2b trucks sold annually is between 5 and 10% of the number of trucks under 8,500 lbs. sold, and it is safe to assume that the average fuel economy of the larger trucks is lower than the average for trucks under 8,500 lbs.9 So the oil savings of S.804 would be at least 510% higher than stated above.10 3. H.R.4 The energy bill passed by the House in August requires the U.S. Department of Transportation to set fuel economy standards for light trucks so as to reduce consumption of oil by 5 billion gallons over the period 20042010 from the consumption that would occur under the current standards. Five billion gallons amounts to 13 days of oil use by U.S. cars and trucks11 at the average projected rate of consumption for the period 20042010, or about 2 days worth of oil per year. CAFE standards in place today, by comparison, save the equivalent of 137 days of oil every year. The 5-billion-gallon provision would presumably continue to save some oil beyond 2010, since the light truck fuel economy standard would need to be raised to meet the oil savings requirement. What that new standard will be is not determined by the bill provision, however, and therefore post-2010 savings are uncertain as well. A very modest hike in the fuel economy of all new trucks starting in 2003 could save 5 billion gallons by 2010, because the benefits would accumulate in the ensuing years as the number of slightly more efficient vehicles, and their number of years on the road, grew. Alternatively, auto manufacturers could take no action until 2006, requiring a much bigger jump in fuel economy in model years 20072010 trucks in order to cut oil use by 5 billion gallons in 4 years. A small, rapid increase in fuel economy is feasible for light truck manufacturers. In 2000, Ford stated that it would raise the fuel economy of its SUVs by 25% by 2005. GM and DaimlerChrysler followed with similar claims. If the "Big Three" were to make good on these commitments,12 the United States would save over 10 billion gallons of oil in 20042010, twice what is required by H.R.4. Since DOT is required to set CAFE standards at the highest feasible level, it follows that the agency would have to implement H.R.4 with a pre-2005 phase-in of a small fuel economy increase for trucks. Unfortunately, this would lead to small long-term oil savings. The average fuel economies of new vehicles (cars and trucks combined) in 2010 under three possible paths to saving 5 billion gallons are shown in Figure 2. A fuel economy increase of 0.7 mpg for all new light trucks in 2003 could meet the requirement of H.R.4; this would amount to a 0.4 mpg increase for the entire new fleet. The second fuel economy provision of the House energy bill is a 4-year extension of the "dual fueled vehicle credit," currently set to expire in 2004. This credit allows auto manufacturers to add up to 1.2 mpg to their average fuel economy, for purposes of CAFE compliance, in return for producing vehicles that are capable of running on alternative fuels. Initially intended to promote the use of fuels such as ethanol, the credit has resulted in the manufacture of many vehicles that can run on alternative fuels in principle, but run on gasoline in fact due to the very limited availability of the non-gasoline fuel they can use. So the dual-fueled vehicle credit has actually increased gasoline consumption by allowing auto companies to produce a fleet that falls short of CAFE standards. Assuming that manufacturers will claim two-thirds of the credit available to them, or 0.8 mpg,13 extending the credit would cost the United States more than 5 billion gallons of oil in 20052008. As a result, the fuel economy provisions of H.R.4 would likely result in a net increase in oil consumption in 20042010. Cumulative oil savings of (1) the 5-billion-gallon savings provision alone (assuming a moderate phase-in of the light truck fuel economy increase), (2) H.R.4 fuel economy provisions together, and (3) the Big Three commitment are shown in Figure 3. 4. Drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge The U.S. Geological Survey released estimates of the volume of oil that would be produced by drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Uncertainties reflected in the analysis include the amount of oil the area contains, the rate at which development would occur, and the price of oil in the future. Their best guess of the amount of "technically recoverable" oil in the relevant portion of ANWR (the "1002 area") is 7.67 billion barrels.14 The amount that is "economically recoverable" is determined by the amount of technically recoverable oil together with its price, which EIA projects will average about $24 per barrel (2000$) in the period 20102020.15 At this price, USGS estimates that 4.4 billion barrels of oil would be economically recoverable from ANWR.16 Using development and production schedules considered moderate by EIA,17 it follows that the extraction of these 4.4 billion barrels would likely unfold as shown in Figure 4 over a period of 51 years. According to EIA, oil resources in certain state waters and Native lands adjacent to the ANWR 1002 area would be developed if and only if drilling proceeds in ANWR itself. These non-federal areas are estimated to contain about 35% as much oil as is in the 1002 area, so their development could raise the total volume of economically recoverable oil to 5.9 billion barrels. According to EIA methodology, production in this larger area would occur over approximately 57 years, and at the rate shown in Figure 4.

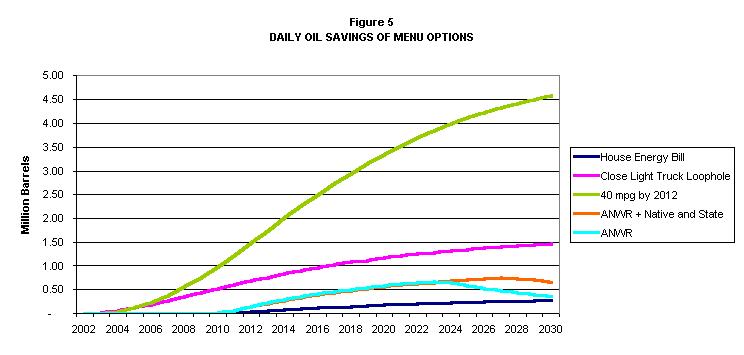

Conclusion Oil savings from a 40 mpg CAFE standard far outstrip the benefits of any of the other proposals and would exceed half of our current car and truck oil consumption in the early 2020s. Figure 5 compares daily oil savings (or production) attributable to the various policy options described above over the period 20022030. Closing the light truck loophole is a clear second, saving about half as much as the 40 mpg standard in the early years and declining to one-third further out. For purposes of comparing oil from ANWR to oil saved through fuel economy requirements over time, we adopt EIA's view that ANWR production would begin in 2010 (at the earliest).18 Drilling in ANWR and adjacent non-federal lands may yield half the amount saved by closing the loophole for a period of 1012 years. Production begins to decline in 2028; if only federal lands are included, the decline begins in 2024. H.R.4 savings are far lower still. Like ANWR drilling, it yields no results until 2010, while the other two CAFE options produce savings beginning in 2003. All three fuel economy provisions save increasing amounts of oil even beyond 2030, because vehicle miles of travel continue to grow. Cumulative savings to 2030 are compared below.

1 This

yields a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) growth slightly below the U.S.

Energy Information Administration's projection of 2.2% per year

averaged over the period 2000-2020. See Annual Energy Outlook

2002, Reference Case Forecast, Table

A7. | ||||||||||||

| Energy

Policy | Programs | Press & Media |

Consumer

Resources Publications & Meetings | Site Map | Home | ||||||||||||

|

Copyright Info Here |