Summary of Traffic Stops Statistics

Chapel Hill Police Department

The following report compiles and presents statistical summaries of traffic stops statistics drawn from the NC State Bureau of Investigation database to which each police agency reports their statistics each month. Data in this report cover the period of 2002 through 2020. The data exclude checkpoint stops because such stops are not recorded systematically. The data also include only the driver of the vehicle, excluding any passengers. Passenger information is generally recorded only in the event of an adverse outcome (e.g., search, arrest).

This report provides the following summary statistics:

First is a table providing summary statistics on numbers of stops, searches, contraband hits, and arrests, as well as relevant rates of these outcomes. This is followed by a series of graphics displaying department and officer level data.

| Summary of outcomes | State-wide | CHPD |

|---|---|---|

| Stops | 24,980,776 | 108,545 |

| Traffic Safety Stops | 13,365,910 | 70,487 |

| Searches | 763,343 | 3,801 |

| Hits | 280,152 | 2,022 |

| Arrests | 500,040 | 2,683 |

| Arrest From Hit From Search | 105,784 | 730 |

| Consent Searches | 346,475 | 908 |

| Arrest From Hit From Consent Search | 20,759 | 66 |

| Probable Cause Searches | 264,963 | 2,219 |

| Arrest From Hit From Probable Cause Search | 54,326 | 519 |

| Percent Traffic Safety Stops | 53.50% | 64.94% |

| Search Rate Per Stop | 3.06% | 3.50% |

| Hit Rate Per Search | 33.48% | 38.25% |

| Arrest Rate Per Hit | 38.85% | 39.81% |

| Hit-and-Arrest Rate Per Search | 13.86% | 19.21% |

| Hit-and-Arrest Rate Per Probable Cause Search | 20.50% | 23.39% |

| Hit-and-Arrest Rate Per Consent Search | 5.99% | 7.27% |

| Arrest Rate Per Stop | 2.00% | 2.47% |

| Hit-and-Arrest Rate Per Stop | 0.42% | 0.67% |

Numbers at top of the table show raw values; numbers below are the percentages based on the numbers above.

Figure 1 shows the total number of stops per year from 2002-2020. Numbers range from just below 2,000 (in 2020) to greater than 8,000 (in 2015). There is a drop associated with the global pandemic in 2020.

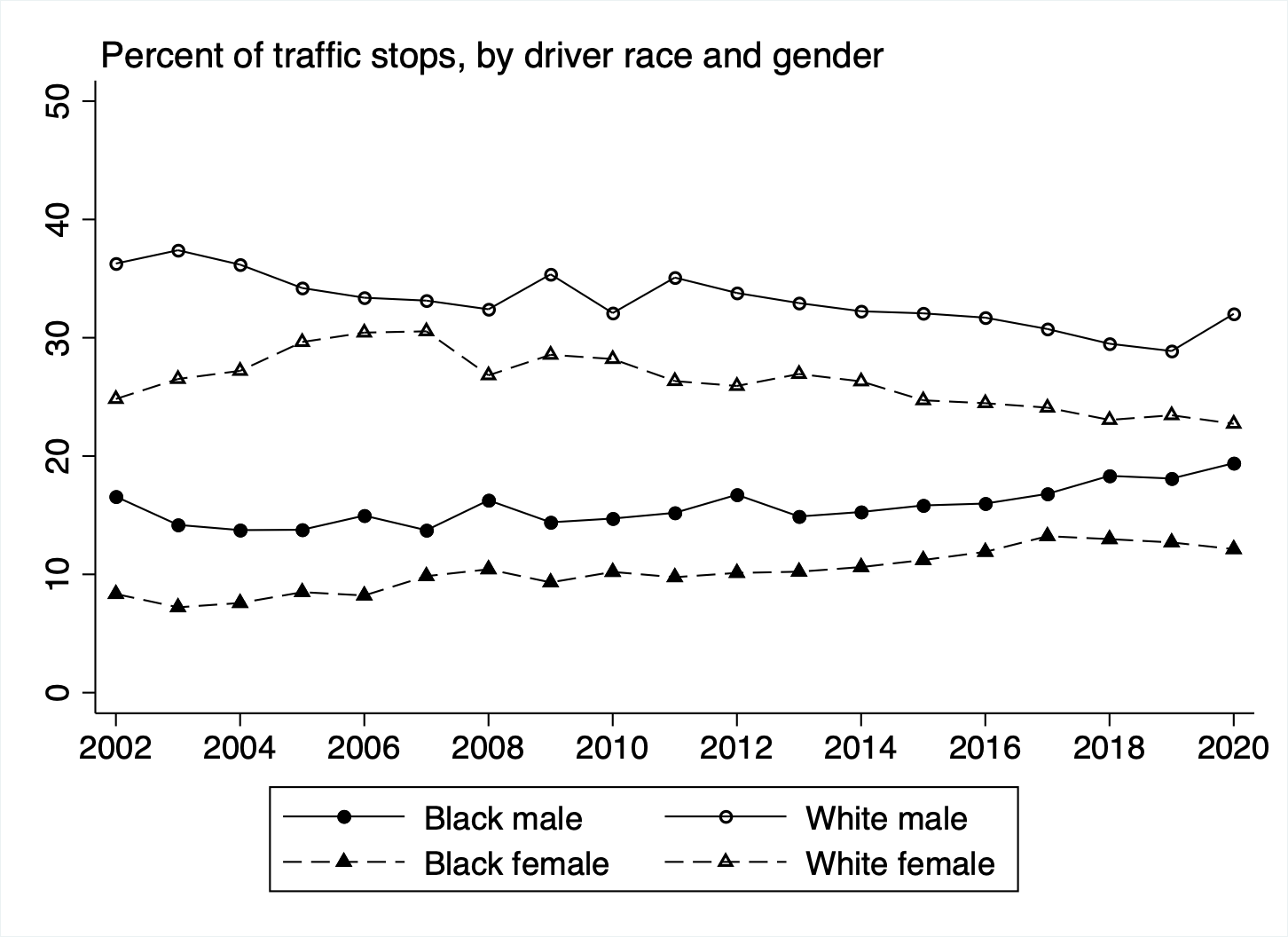

Figure 2. Percent of stops by race-gender category

Figure 2 shows the total number of traffic stops by race and gender from 2002-2020. For example, in 2002, roughly 37% of total traffic stops were of white males, roughly 17% of stops were of black males, roughly 9% were of black females, and roughly 25% were of white females. All drivers’ share of those stopped was relatively stable across the timeframe, with no significant increases or decreases.

Figure 3. Percent of stops for “safety” purposes (speeding, stop sign, DUI, unsafe movement)

Figure 3 shows the percentage of traffic stops that are considered safety-related for each respective race and gender grouping, from 2002-2020. Safety-related spots are composed of stops due to speeding, stop sign violations, DWI, and unsafe movement. Stops for violations other than this are classified as non-safety related. These are composed of non-moving violations such as equipment violations and expired tags. For this reason, non-safety-related stops can be considered to be used as informal criminal investigations. Each race and gender group followed relatively similar trends across the time period. The year to year change had great variation for all categories, with sharp increases and decreases in the percent of safety-related stops being common. Chapel Hill also saw much less consistency between categories relative to comparable departments. For example, from 2010 to 2011, black males saw a decrease in safety-related stops, while all other groups saw an increase. Overall, black male consistently had the lowest percentage of their stops classified as safety-related. Black females typically had the second lowest percentage of safety related stops, but were often comparable to white male drivers. White female drivers typically had the highest percentage of safety related stops.

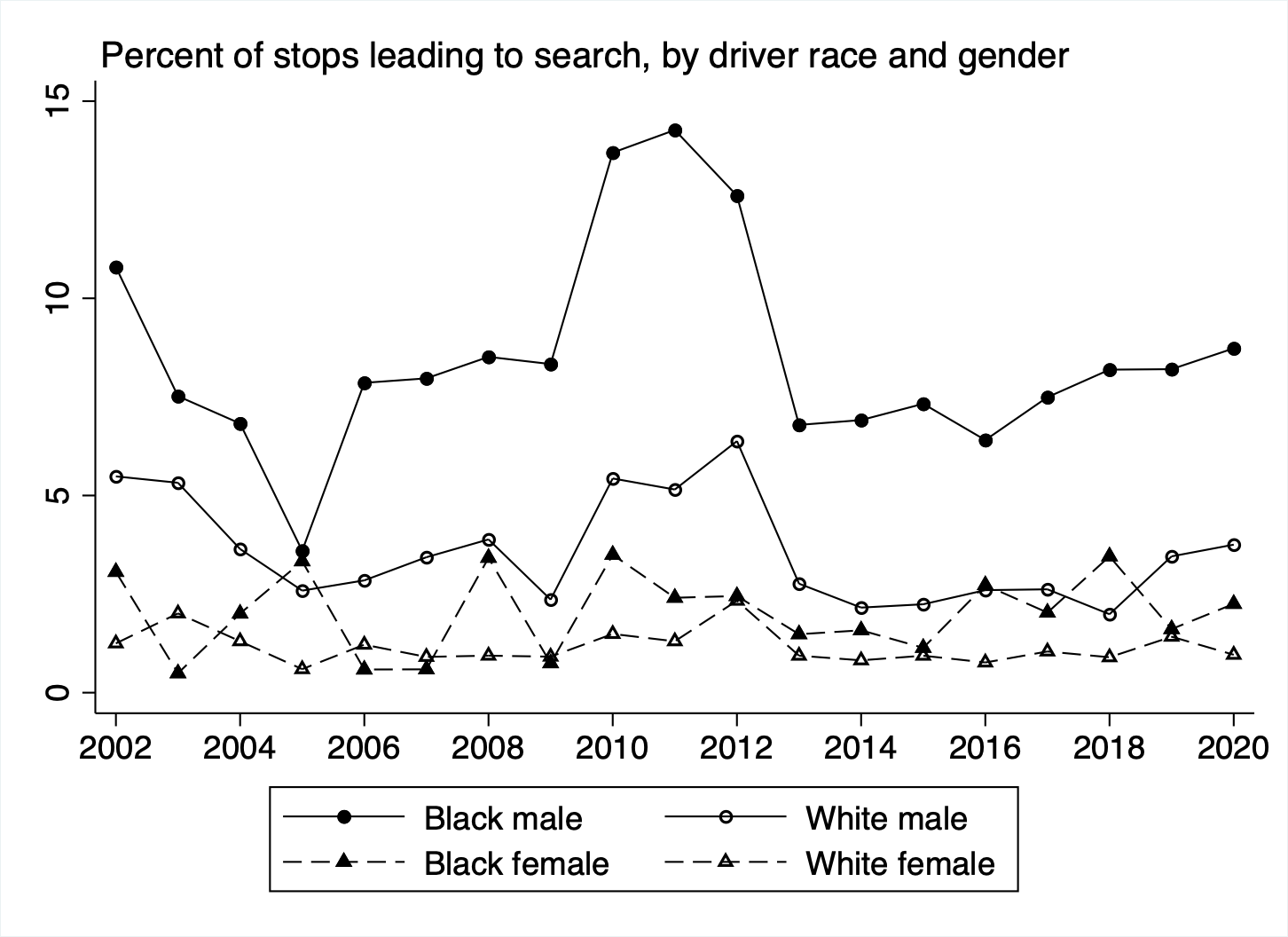

Figure 4. Percent of stops resulting in a search, by race-gender category

Figure 4 shows the percent of traffic stops that result in a search for each respective race and gender grouping, from 2002-2020. The Figure indicates that most traffic stops do not result in a search. For all categories except black males, drivers were searched at less than a 6% rate across the time period. Black males were typically searched at higher rates, ranging from 4 to just below 15% across the time period. In most years, their search rate fell between 5 and 10%. This is significantly more often then the second most searched group, white males, who were searched in 2 to 6% of stops. White and black female drivers typically were searched at the lowest rates. In a few instances, black females were searched slightly more often than white males, such as in 2005 and 2018.

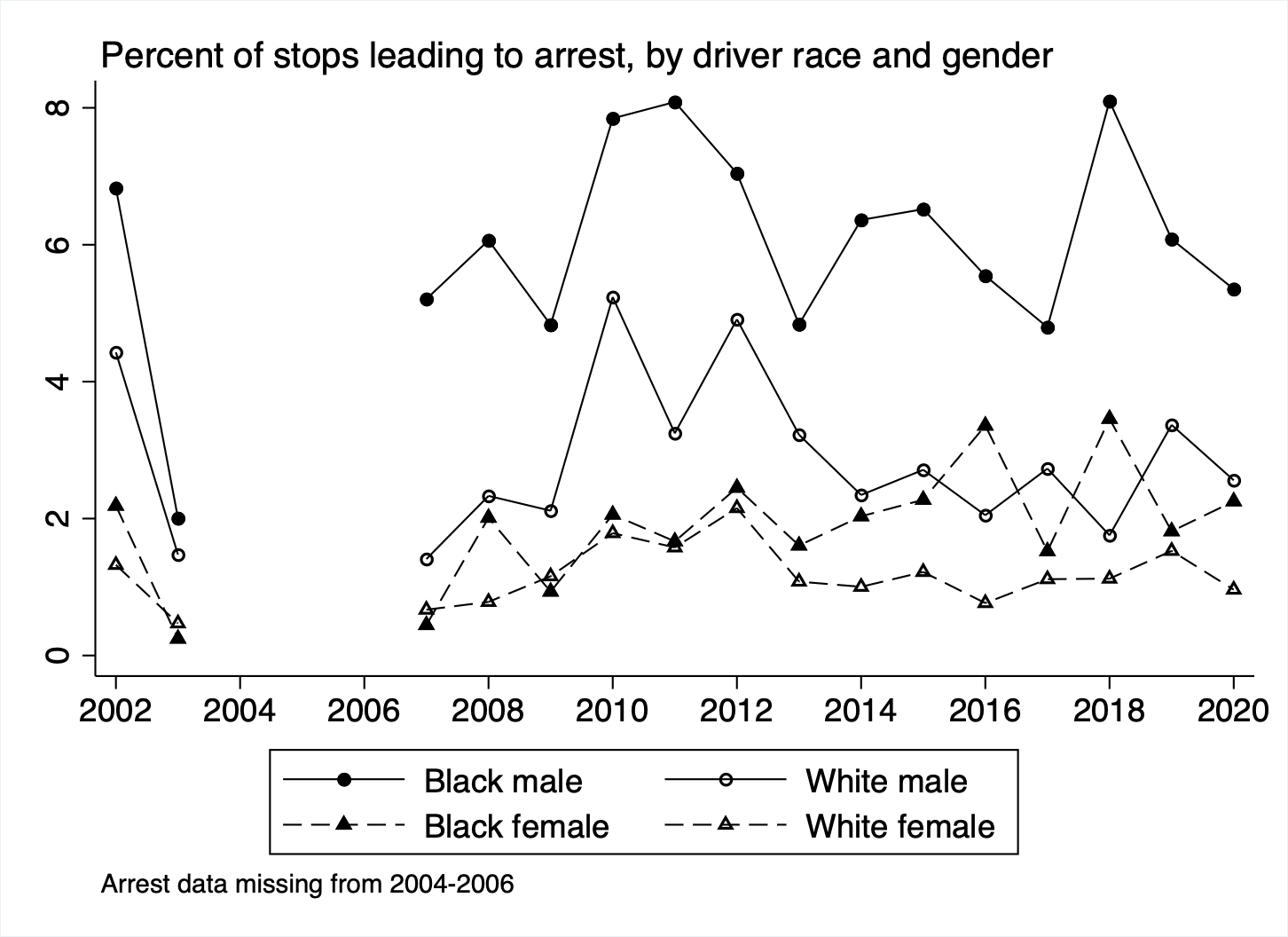

Figure 5. Percent of stops resulting in arrest, by race-gender category

Figure 5 shows the percent of traffic stops that result in an arrest for each respective race and gender grouping, from 2002-2020. Across the board, arrest rates are consistently very low, at 8% or below for all categories across the time period. Black males are arrested at the highest rate in every year, and their arrest rate ranges from 2 to 8%, although the rate was generally between 4.5 to 8%. Arrest rates for the other race and gender categories range from 0 to 6%. For the first half of the time period, white males were typically arrested at the second highest rate. Post-2014, however, white males and black females were both equally likely to be the second most arrested group, with each category surpassing the other on a year to year basis. White females were arrested at the lowest rate during this portion of the time period. From 2004 to 2006, arrest data is missing and therefore is not displayed in the Figure.

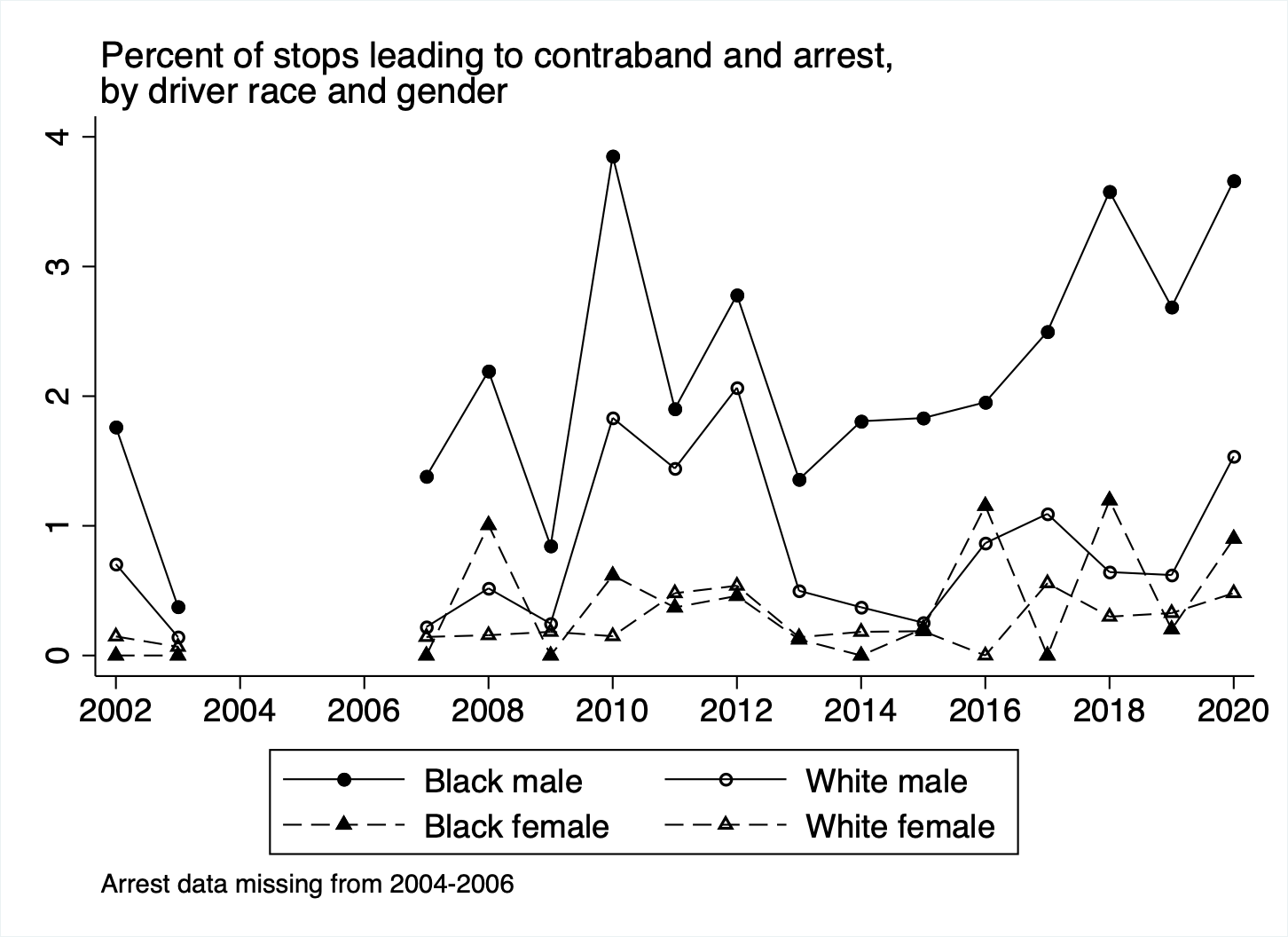

Figure 6. Percent of stops resulting in contraband and arrest, by race-gender category

Figure 6 shows the percent of stops that resulted in the discovery of contraband and an arrest for each respective race and gender grouping, from 2002-2020. The rates are very low for each category. White males, white females, and black females all have rates of less than 2% across the time period. The rates for black males are slightly higher but do not surpass 4%, with great year to year variation. For white males, contraband and arrest occur at a rate similar to female drivers in a majority of the time period, with the main exception being from 2010-2012. Overall, for all race and gender categories, traffic stops are overwhelmingly unlikely to result in contraband and arrest. From 2004 to 2006, arrest data is missing and therefore is not displayed in the Figure.

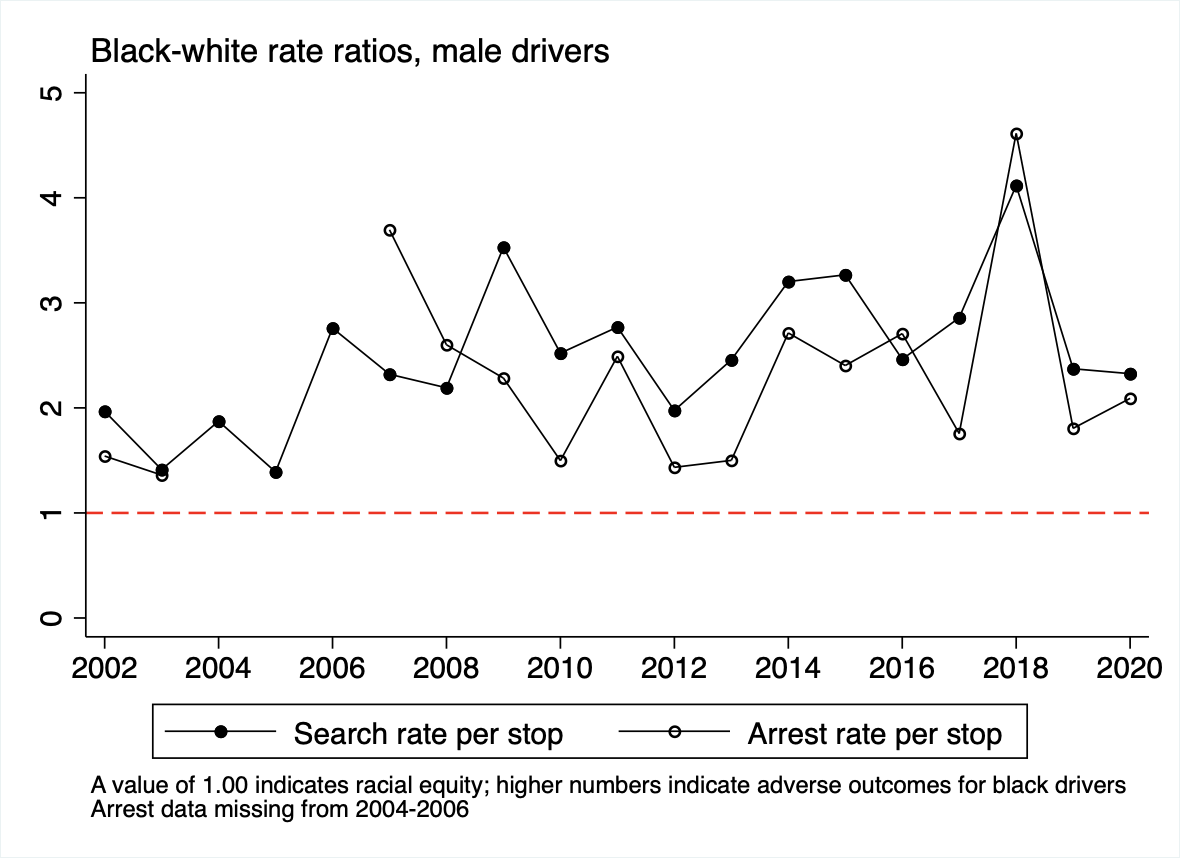

Figure 7. Black-White Ratio of search rates and arrest rates, for males

Figure 7 compares the search rate and arrest rate of black males and white males from 2002-2020. The search rate ratio is the search rate of black males divided by the search rate of white males, while the arrest rate ratio is the arrest rate of black males divided by the arrest rate of white males. A search rate ratio of 1.0 would indicate that black and white males are both searched in an equal percentage of their respective traffic stops. This similarly applies for the arrest rate ratios. Across the time period, the search rate ratio is consistently above 1, and is often much greater. This means that black males are searched much more frequently than white males across the time period. The search rate ratio peaked at roughly 4 in 2018, and typically ranged from 2 to 4. The arrest rate ratio also is consistently above 1. The arrest rate ratio does surpass the search rate ratio in certain instances, such as 2007 and 2018, but typically is lower than the search rate ratio across the period. This means that in most years recorded, black males are arrested at a greater rate than white males, but not to the degree that they are disproportionately searched. From 2004 to 2006, arrest data is missing and therefore there is no arrest rate ratio for these years.

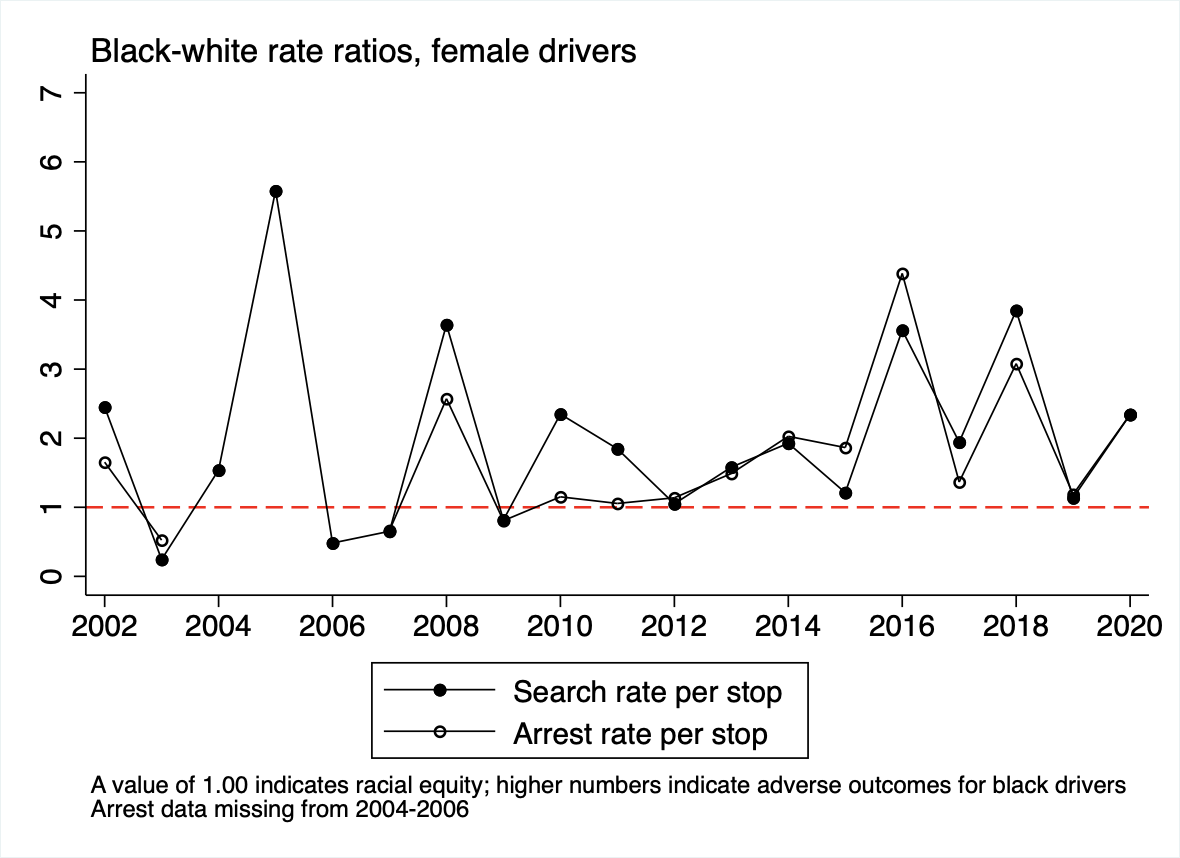

Figure 8. Black-White Ratio of search rates and arrest rates, for females

Figure 8 compares the search rate and arrest rate of black females and white females from 2002-2020. The search rate ratio is the search rate of black females divided by the search rate of white females, while the arrest rate ratio is the arrest rate of black females divided by the arrest rate of white females. A search rate ratio of 1.0 would indicate that black and white females are both searched in an equal percentage of their respective traffic stops. Across the time period, the search rate ratio ranges from about 0.2 to almost 6. The arrest rate ratio ranges from about 0.6 to just above 4. Both ratios fluctuate greatly on a yearly basis. In certain instances, the ratios both appear to follow a similar pattern, such as from 2012 to 2020. From 2004 to 2006, arrest data is missing and therefore there is no arrest rate ratio for these years.

Figure 9. Summary of stops by hour over the week: Stops, percent safety-related, percent ending in citation, search, and arrest

Figure 9 displays the number of traffic stops, the percent of safety related stops, the percentage of drivers receiving a citation, the percentage of drivers searched, and the percentage of drivers arrested across the hours of the week. The Figure indicates that there is not much variation between the days of the week in regard to these measures, and instead shows that the variation is seen within the hours of the day. There are a few noticeable trends throughout the week, however. Stops occur at the highest rate during the daytime hours on Tuesday. Search rates are highest during the early morning hours of Wednesday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday as compared to the rest of the week at the same time. Arrest rates are highest on the very early morning on Saturday, as compared to the same time on other days.

Figure 10. Summary of stops by hour over the day: Stops, percent safety-related, percent ending in citation, search, and arrest

Figure 10 displays the number of traffic stops, the percent of safety related stops, and the percent of drivers searched, given a citation, and arrested by hour of day. There are a number of clear trends indicated in the Figures. The frequency of a traffic stop is lowest in the early hours of the morning, from around 4AM to 6AM. The number of traffic stops increases steadily until 11AM, at which the frequency is relatively similar until around 4PM, with a few minor changes throughout the daytime. The frequency of stops then drops until 6PM, and then once again increases till 10PM. This level is maintained until 2AM, at which point the stop frequency then drops in the following hours.

The percentages of drivers searched and arrested both have a similar trend across the time of day. Drivers are both searched and arrested at the highest rate in the few hours after midnight, and then these rates of search and arrest decrease dramatically from 5AM to 7AM. After 7AM, the rate of both search and arrest is at extremely low percentages, and these rates then slowly increase for the remainder of the day.

The percentage of drivers receiving a citation follows an opposite trend of search and arrest rates. The rate of citations given is at its lowest from 8PM to 5AM. The rate then sharply increases from 5AM to 7AM, and remains high for the remainder of the day, slowly beginning to decrease at 3PM until nighttime. The rate is significantly higher during daytime hours as compared to nighttime hours.

The percent of safety-related stops varies throughout the day, reaching its highest point at 6AM, and staying at an elevated level until 3PM. After 3PM, the rate of safety-related stops decreases until 7PM, and stays at this level until 10PM. At 10PM, the percentage of safety-related stops begins to increase until the early morning high.

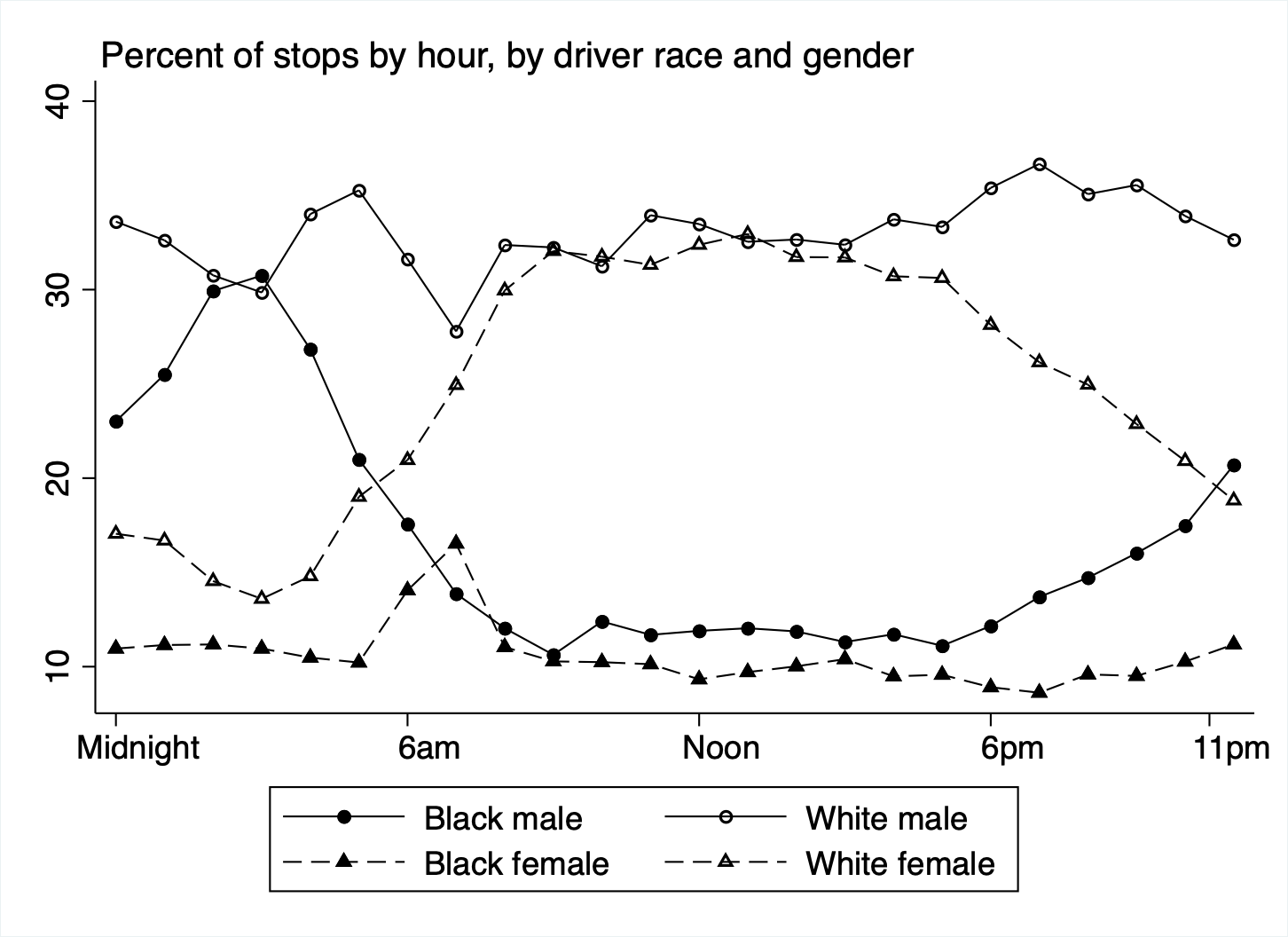

Figure 11. Hourly breakdown of percent of stops by race-gender category

Figure 11 displays the share of overall stops represented by the respective race and gender categories by hour of day. The Figure indicates that white males make up the highest percentage of stops across the day, at typically just above 30% throughout the day. The Figure also indicates that black males are significantly more likely to be stopped during the nighttime hours directly before and after midnight than they are to be stopped during the daytime. At 3AM, black males reach a high of more than 30% of those that are pulled over, and by 7AM their share of stops decreases to almost 10%, and stays at a lower proportion of stops throughout the daytime hours. Black females make up a relatively consistent share of traffic stops throughout the day, at around 10%, with a slightly increased stop frequency from 6AM to 7AM. White females see a significant uptick in their proportion of stops during the daytime hours, going from below 20% during the nighttime hours to about 30% during the daytime, with rates comparable to white males during this portion of the day.

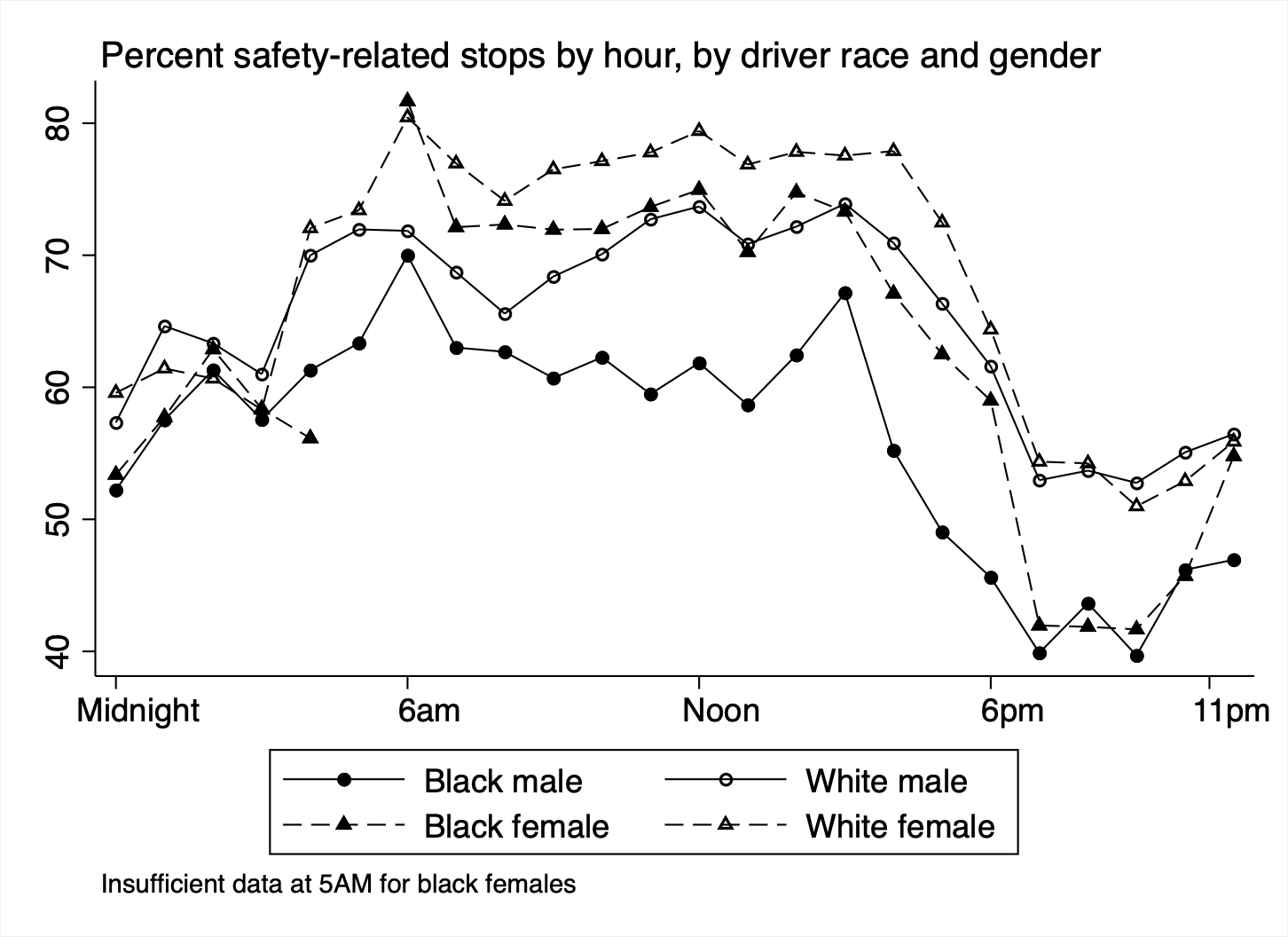

Figure 12. Hourly breakdown of percent of stops related to traffic safety, by race-gender category

Figure 12 displays the percentage of stops that are for safety-related purposes for each race and gender category, by hour of the day. Safety-related purposes refer to traffic stops that are meant to prevent moving violations, and effectively keep the road safe. Stops that are not safety-related are often used for investigatory purposes, in which case the officer is generally seeking to conduct an informal criminal investigation of the driver. As evidenced in the Figure, black males are less likely to be stopped for safety-related purposes than other drivers throughout the course of the day, with the only exception coming during the hours directly after midnight, when all drivers share relatively comparable rates. However, during the nighttime hours after 5PM, black females are also less likely to be stopped for safety-related purposes than white drivers. In turn, this means that black drivers (specifically black males) are more likely to be subjected to investigative stops that are not for moving violations. The rate of safety-related stops is higher for all drivers during the daytime hours. For much of the daytime, white females have the highest rate of safety-stops, while black females and white males have a similar percentage of stops classified as such. At 5AM, black females have insufficient data and therefore are not displayed.

Figure 13. Hourly breakdown of percent of stops resulting in search, by race-gender category

Figure 13 displays the percentage of traffic stops which result in a search for each race and gender category, by hour of the day. During the early morning hours directly after midnight, all drivers experience higher search rates, with males experiencing the highest rates. From midnight to 2AM, black drivers are searched at the highest frequency, but they are surpassed by white males from 3AM to 5AM. During the daytime hours, while all drivers experience lower rates of search as compared to the early morning, black males have significantly higher search rates as compared to all other drivers. White males and all female drivers have a similar percentage of stops leading to a search from 7AM to 11PM, at below 5%. During this portion of the day, black males are typically searched in 5 to 10% of stops. The Figure also indicates that a majority of stops do not result in a search regardless of race and gender category or time of day.

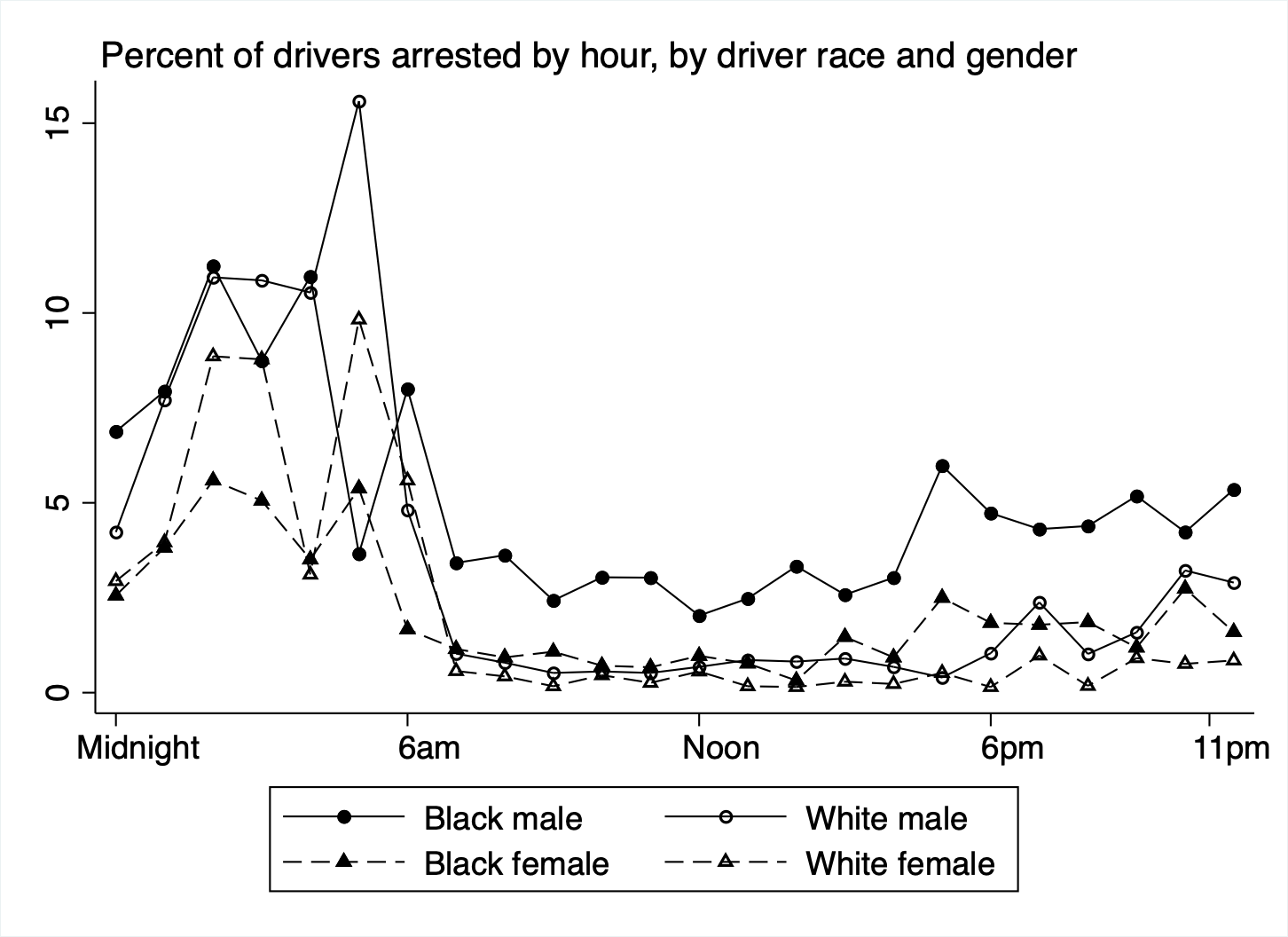

Figure 14. Hourly breakdown of percent of stops resulting in arrest, by race-gender category

Figure 14 displays the percentage of traffic stops which result in an arrest for each race and gender category, by hour of the day. For all categories, drivers are more likely to be arrested during nighttime hours, specifically the hours following midnight. Overally, stops are most likely to result in an arrest from midnight to 6AM. Throughout the daytime hours and the nighttime hours preceding midnight, white males and all females are arrested at similar rates. Black males, however, are arrested at higher rates during this period. The Figure also indicates that a large majority of stops do not result in an arrest regardless of race and gender category or time of day.

Figure 15. Number of stops by officer

Figure 15 displays the distribution of number of stops by officer across the 2002-2020 time period. All officers displayed have over 100 traffic stops. 122 of the 145 officers included in the data have less than 1000 traffic stops.

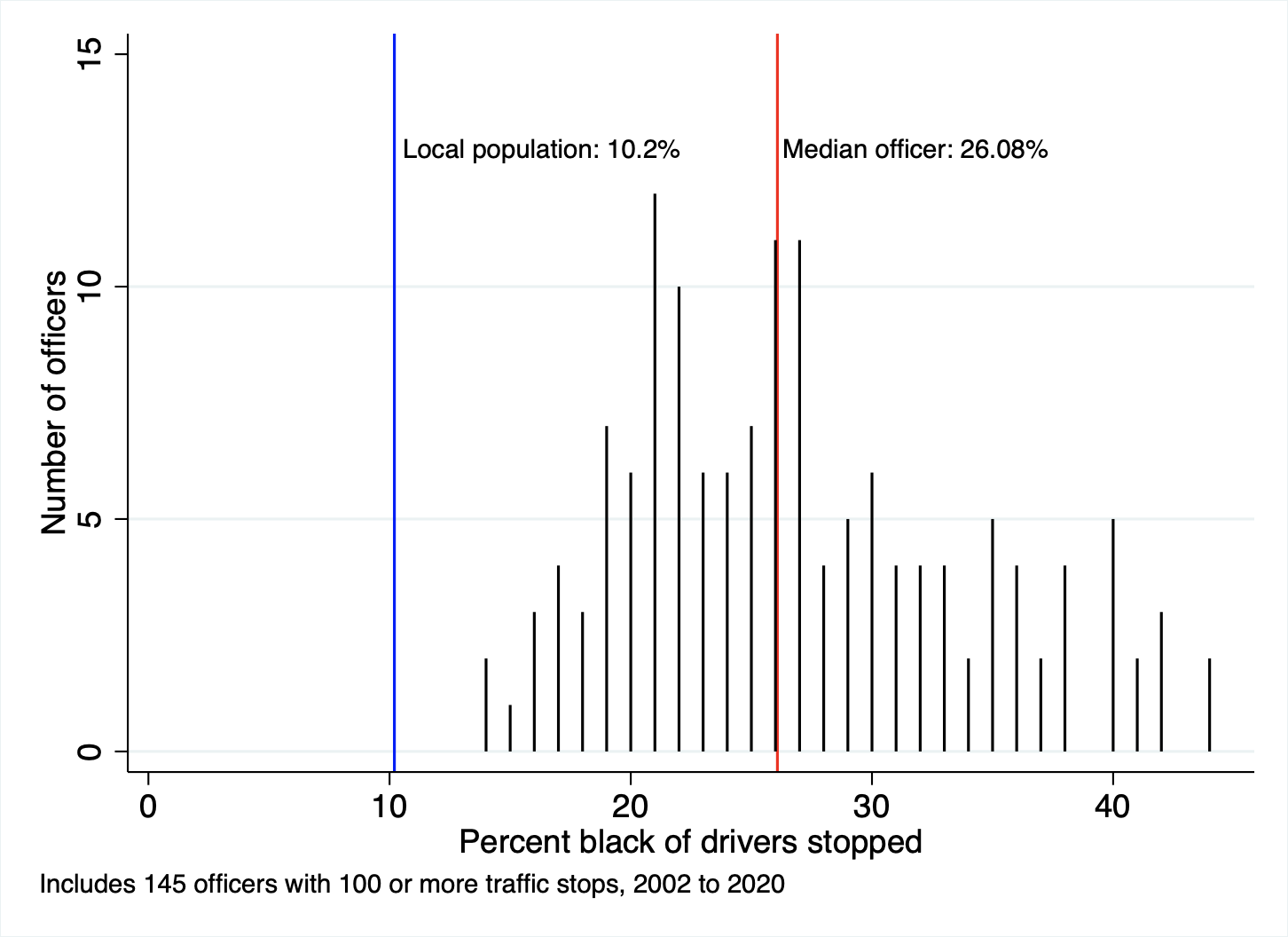

Figure 16. Percent black of drivers pulled over by officer

Figure 16 displays the percentage of stopped drivers that are black for individual officers, from 2002-2020. The distribution includes officers with greater than 100 traffic stops. For the median officer, 26.08% of stops are of black drivers, while black people only make up 10.2% of the population in the city. This means that officers are stopping black drivers at a rate disproportionate to their share of the population. In the case of Chapel Hill, every single officer with 100 or more traffic stops stops black drivers at a higher rate than their share of the population. This disparity between stop behavior and population data is also often greater, with black drivers composing more than 35% of stops for a significant portion of officers. At the far right, the Figure shows that there are 26 officers whose mix of drivers stopped is more than 35% black.

Figure 17. Officer search rates by race

Figure 17 displays the search rates of individual officers for the given race and gender category. The criteria for an officer’s inclusion is 100 or more traffic stops, as well as at least 50 stops of the specified race and gender category, from 2002-2020. In the first graph, which displays search rates for black males, the median officer has a search rate of 6.93%. For white male drivers, the median officer has a search rate of 2.56%. This indicates that the median officer in Chapel Hill is searching black males at a higher rate than they are searching white males.

Figure 18. Black-White Ratio of search rates by officer, for males

Figure 18 displays the distribution of black-white male search rate ratios across the officers which meet the criteria. The criteria for an officer’s inclusion is 50 traffic stops of both white males and black males, from 2002-2020. The “Black-white male search rate ratio” can be interpreted as an officer’s search rate of black male drivers divided by their search rate of white male drivers. An racially equitable outcome would therefore be 1, meaning that black and white male drivers are searched in an equal percentage of traffic stops. The median officer instead has a search rate ratio of 1.83, meaning that the median officer searches black male drivers at a higher rate than white male drivers. A significant number of officers have search-rate ratios that are much higher than the median, with a large portion searching black male drivers at 3 or more times the rate of white male drivers.

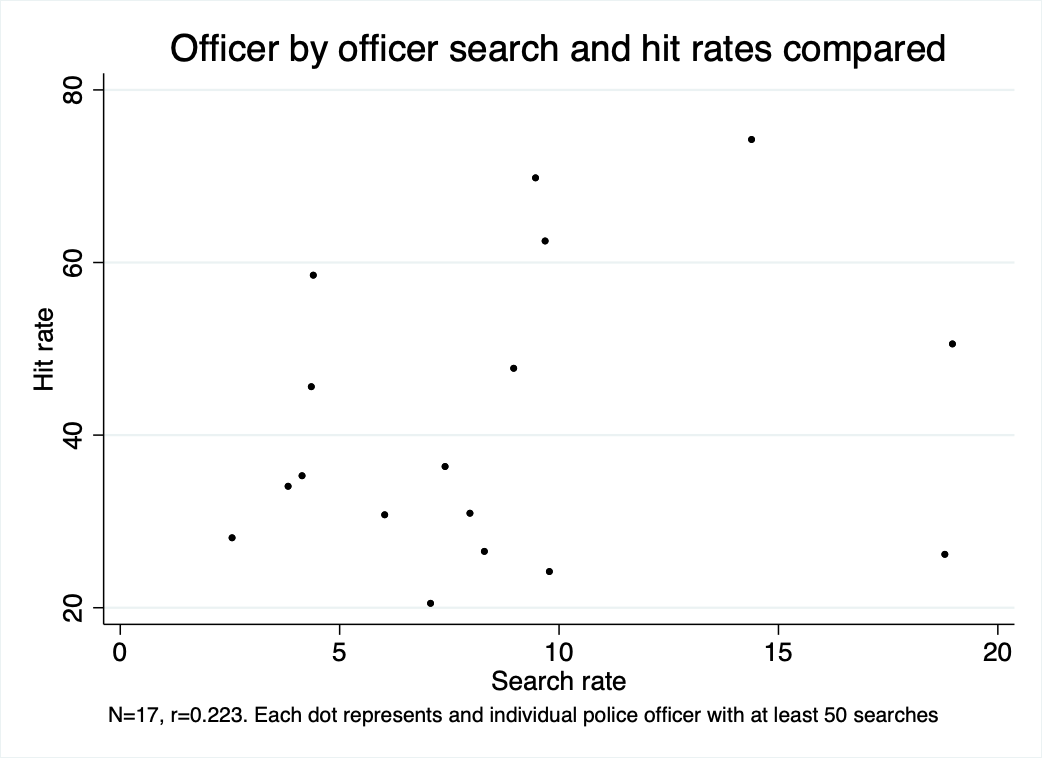

Figure 19. Search rate versus hit rate by officer

Figure 19 presents the hit rates and search rates of individual officers who meet the criteria. As evidenced by the low correlation, there is great variability in both the propensity of individual officers to search drivers and their success in finding contraband. One might expect that when officers have a high search rate but a low hit rate, that their supervisors would advise them to adjust their search rate in order to avoid so many fruitless searches. Similarly, for officers with low search rates but high hit rates, one might expect supervisors to instruct them to conduct more searches because they are being too cautious. Such a learning process would generate relative consistent hit rates; where officers are too high, they would be advised to do more searches, and where too low, to conduct fewer. The Figure shows clearly that this is not happening. Search and hit rates range from low to high, with a very low correlation between the two. Certain officers search drivers at extremely high rates but have very low hit rates, meaning that their threshold of suspicion is likely too low. Other officers search at a much lower rate and have very high hit rates, showing that their threshold of suspicion may be too high. Overall, the Figure shows that officers are not gravitating towards a single common range of hit rates. This suggests that the department does not seem to hold its officers to a common standard of search rate success. Rather, each officer decides for him or herself how aggressive to be in searching, with virtually no guarantee that more searches will lead to lower hit rates, or that fewer searches will be targeted on those most likely to have contraband.